Findings shed new light on why Zika causes birth defects in some pregnancies

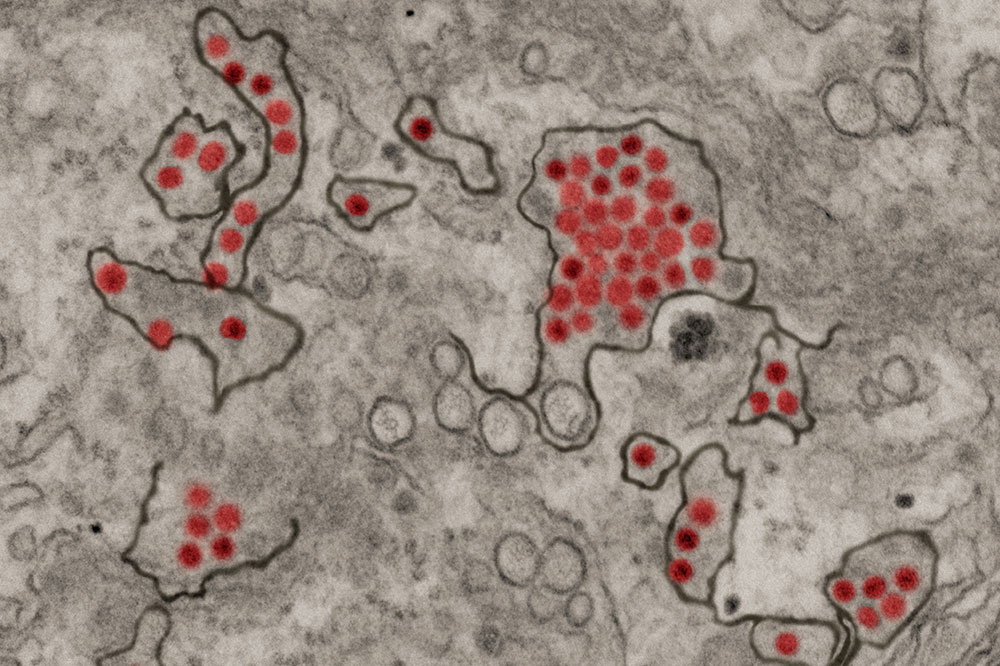

Kidney cells infected with Zika (red), a virus that can cause severe birth defects if it spreads from a pregnant woman to her baby.

One thing is clear when it comes to Zika: Pregnant women must do everything they can to avoid getting infected. If the virus gains entry to the mother’s cells, it can also infect the baby and cause severe birth defects, typically with a condition known as microcephaly in which the head is underdeveloped.

What is less clear is why many infected mothers nevertheless give birth to normal-looking children. In fact, only about five percent of infants delivered by women with Zika are born with microcephaly.

Now, a team of Rockefeller scientists say the reason for this difference might reside in the mother’s antibodies. In a study reported in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, the researchers show that the risk of giving birth to a child with microcephaly might be related to how the immune system reacts against the virus—specifically what kind of antibodies it produces.

It’s an insight that could have important ramifications for ongoing efforts to develop a Zika vaccine.

The related-virus theory

Previously, some scientists have suggested that Zika-induced birth defects may be linked to mothers’ experiences with some other mosquito-borne viruses, including the dengue and West Nile virus, which are similar to Zika. The reasoning went that if a woman contracted and survived a first infection with dengue, for example, and then later became infected with Zika during pregnancy, antibodies that had once fought off dengue might still be in her system. Such antibody remnants were suspected capable of reacting against the Zika virus in an undesirable way, harming the baby rather than protecting it or the mother from disease.

But when research associate professor Davide F. Robbiani and his colleagues analyzed blood samples from around 150 pregnant women with the virus—all collected in Brazil during the country’s 2015 Zika outbreak—they found no evidence for a connection between birth defects and history of related viruses. Instead, they discovered that antibodies generated against the Zika virus itself may be to blame.

In mothers who delivered babies with microcephaly, such Zika-specific antibodies carried molecular features that seemed to correlate with the condition. This finding was later confirmed in animals suggesting that, rather than protecting the body from Zika, some antibodies may in fact help the virus enter maternal cells, increasing the risk of fetal brain damage.

New vaccine challenges

“Although our results only show a correlation at this point, there could be significant implications for vaccine development,” says Robbiani, who led the international study together with Michel C. Nussenzweig, the Zanvil A. Cohn and Ralph M. Steinman Professor.

There is currently no approved vaccine against Zika and, in light of the new findings, developing one could turn out to be trickier than experts previously realized. “A safe vaccine would need to induce the immune system to selectively produce antibodies that are protective, avoiding those that potentially enhance the risk of microcephaly,” Robbiani says.

As a first step toward this goal, he is conducting further research to establish which types of antibodies might be harmful to unborn babies, and by what mechanisms they promote fetal damage.