Our History

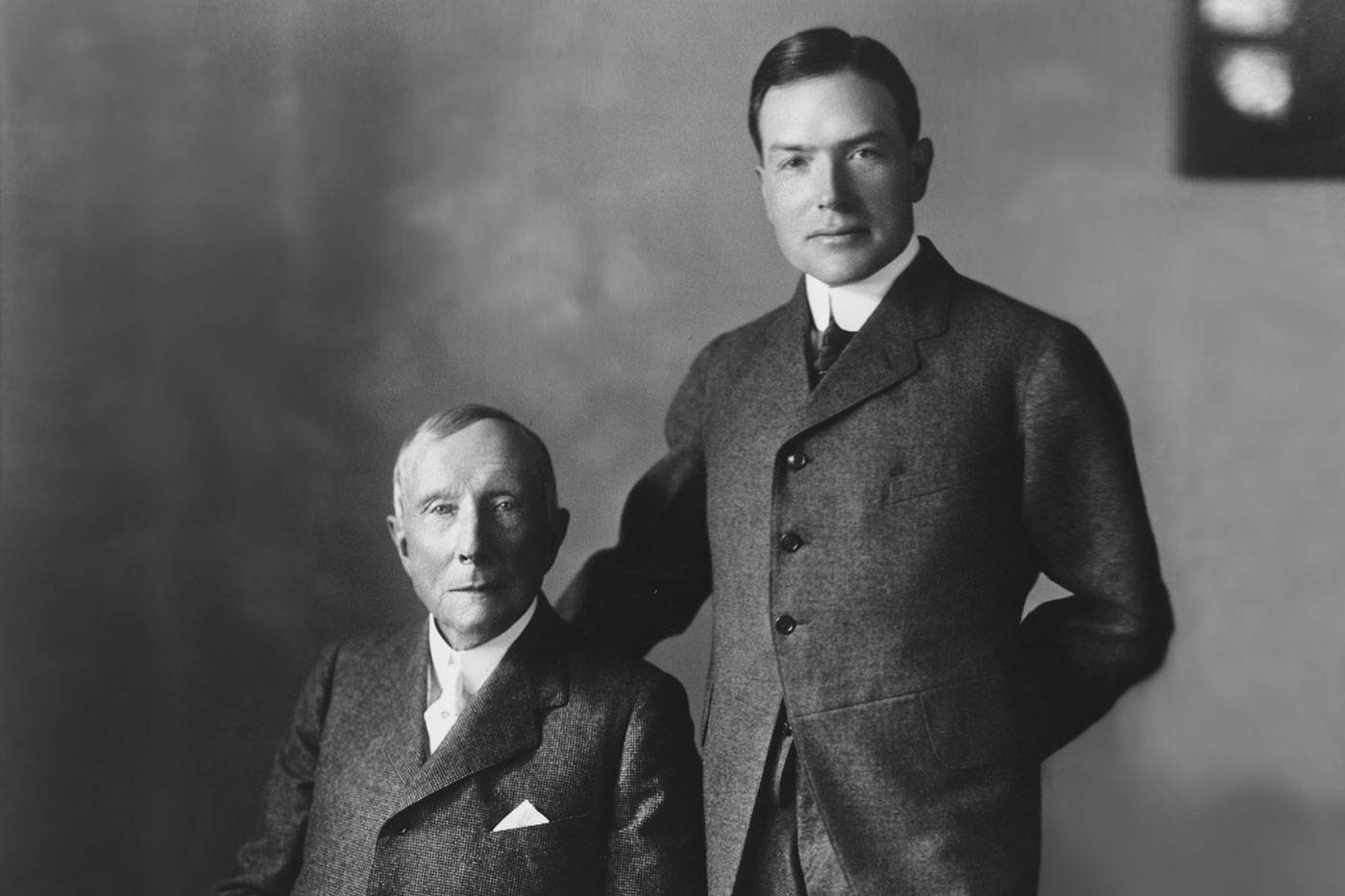

A Philanthropist’s Vision Becomes Reality

The origins of the university lie, in part, in personal tragedy. After John D. Rockefeller Sr.’s grandson died from scarlet fever in January 1901, the capitalist and philanthropist formalized plans to establish the research center he had been discussing for three years with his adviser Frederick T. Gates and his son John D. Rockefeller Jr. At the time of the institute’s founding, infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, diphtheria, and typhoid fever were considered the greatest known threats to human health. New research centers in Europe, including the Koch and Pasteur Institutes, were successfully applying laboratory science to increase our understanding of those and other diseases. Following their lead, The Rockefeller Institute became the first biomedical research center in the United States.

At first, The Rockefeller Institute awarded grants to study, among other public health problems, bacterial contamination in New York City’s milk supply. After two years in temporary quarters, laboratories were opened in 1906 on the site of the former Schermerhorn farm at York Avenue (then called Avenue A) and 66th Street. From the beginning, Rockefeller researchers made important contributions to understanding and curing disease. Simon Flexner, the first director of the institute, developed a novel delivery system for an anti-meningitis serum; Hideyo Noguchi studied the syphilis microbe and searched for the cause of yellow fever; Louise Pearce developed a drug to use against African sleeping sickness; and Peyton Rous deduced that cancer can be caused by a virus.

A New Kind of Hospital

The Rockefeller Institute Hospital, crucial to the institute’s mission, opened in 1910. The first center for clinical research in the United States, it remains a place where researchers can link laboratory investigations with bedside observations to provide a scientific basis for disease detection, prevention, and treatment. Early on, researchers at the hospital studied polio, heart disease, and diabetes, among other diseases. This special hospital environment served as the model for dozens of other clinical research centers established in the next decades.

Landmark Science

In 1913, Oswald T. Avery came to The Rockefeller Institute Hospital to study differences in virulence among strains of pneumococcus, a bacterium that causes severe pneumonia. Dr. Avery’s research led to the development of the first vaccine for pneumococcal pneumonia, but it also led him and colleagues Colin M. MacLeod and Maclyn McCarty to make an unexpected discovery in 1944: that DNA is the substance that transmits hereditary information, a finding that would set the course for biological research for the rest of the century.

Other Rockefeller researchers modernized the science of cell biology in the 1940s and 50s. Making use of the newly developed electron microscope, which provided magnification hundreds of thousands of times that of traditional light microscopes, Rockefeller scientists were the first to see inside cells. They demonstrated that the fluid inside cells, which once had been considered an undifferentiated chemical soup, contain unique structures that carry out distinct functions that cells need to live. Together, these scientists ushered the science of cell biology into the modern era.

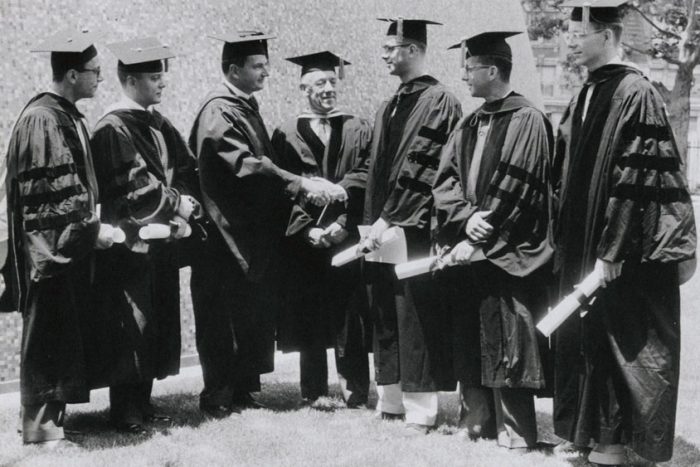

A University Is Born

In 1955, The Rockefeller Institute expanded its mission to include education and admitted its first class of graduate students. It granted its first doctoral degrees in 1959. In 1965, The Rockefeller Institute became The Rockefeller University, broadening its research mandate further. In the early 1960s, new faculty with expertise in physics and mathematics came to Rockefeller and in 1972, the university began its collaboration with Cornell University to offer graduate students an M.D.-Ph.D. program. Later, the Sloan-Kettering Institute became a partner in what is now known as the Tri-Institutional Program. Since its first Convocation ceremony in 1959, when five doctorates were conferred, the university has granted more than 1,000 Ph.D. degrees to students who have gone on to influential positions in academia, industry and other fields.

Scientific Excellence Continues

While Rockefeller is actively dedicated to educating the next generation of scientists, biomedical research has remained at the center of the university’s mission. Like their predecessors early in the 20th century, some Rockefeller researchers have sought to solve urgent public health problems. Others have focused on basic research. During the 1960s, ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, Rockefeller scientists:

- discovered the dendritic cell, the sentinel of the immune system;

- showed that an adult brain of a higher species can form new nerve cells;

- identified a genetic defect associated with atherosclerosis, the leading cause of heart attacks in the U.S.;

- discovered that chronic stress causes brain cells to shrink;

- determined the chemical structure of antibodies;

- pioneered the physiology and chemistry of vision;

- located genes regulating the sleep/wake cycle; and

- identified genes influencing obesity.

In the last decade alone, Rockefeller researchers have

- uncovered the molecular basis of fragile X syndrome, the second leading cause of intellectual disability;

- developed a powerful agent that can target and wipe out anthrax bacteria;

- produced an infectious form of the hepatitis C virus in laboratory cultures of human cells, leading directly to three new classes of hepatitis C drugs;

- showed that a normal strain of staph bacteria required only 90 days to mutate and gain antibiotic resistance;

- discovered a new link between depression and serotonin, a brain chemical that regulates mood, sleep, and memory; and

- imaged for the first time the birth of HIV particles in a living cell.