Leptin Helps Body Regulate Fat, Links to Diet

Leptin, a protein produced by fat, appears to play an important role in how the body manages its supply of fat, report scientists in the November Nature Medicine.

Leptin, a protein produced by fat, appears to play an important role in how the body manages its supply of fat, report scientists in the November Nature Medicine.

“We found the amount of leptin highly correlates to how much fat is stored in the body, with greater levels found in individuals with more fat and reduced levels in those who dieted,” says senior author Jeffrey Friedman, M.D., Ph.D., professor at The Rockefeller University and an associate investigator with Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). “However, not all obese patients have increased levels, which suggests there may be important differences in the cause of obesity.”

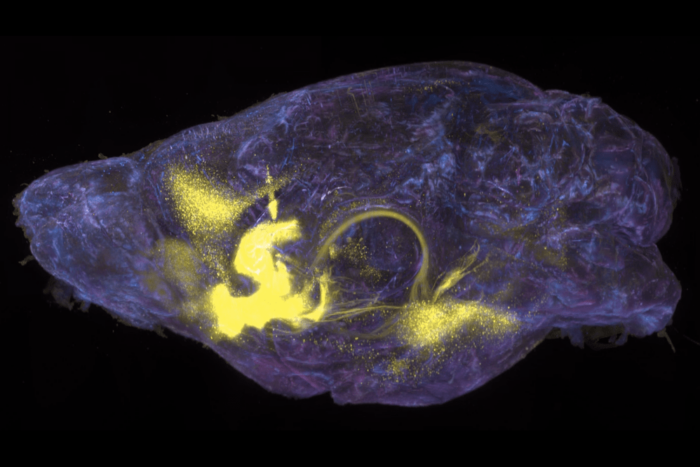

Friedman and his colleagues think leptin acts as a signal of how much fat is in the body to the brain’s hypothalamus, which coordinates basic body functions such as eating. Differences in the fat’s production rate of leptin, resistance to leptin at its site of action or a combination of these factors could influence eating behaviors and energy use to cause obesity or other nutritional abnormalities, such as diabetes, the researchers suggest.

Reduced sensitivity to leptin in some patients could explain why more leptin is found in obese people, the scientists note. “Some obese people may make leptin at a greater rate to compensate for a faulty signaling process or action,” Friedman says. “If resistance to leptin is partial, rather than complete, more leptin may be required for action.”

In addition, obesity may occur if genetic or environmental factors affect body chemistry after leptin acts, notes lead author Margherita Maffei, Ph.D., postdoctoral associate in Friedman’s laboratory.

Leptin’s signaling ability may also help explain the high rates of regaining weight found among dieters, the investigators report. “After dieting, the levels of leptin drop, suggesting that less leptin is made and available to signal the brain,” Friedman says. “This reduction may contribute to increased hunger and slower metabolism. If this is true, leptin therapy may help people maintain weight loss after dieting. However, we first must continue with studies to determine the safety of leptin as a possible therapy.”

The researchers previously published a study documenting a 30 percent weight loss in genetically obese mice given daily injections of leptin for two weeks. While receiving leptin, the mice ate less and increased their use of energy.

The instructions to make leptin are found in the obese (ob) gene. Friedman and his colleagues cloned theob gene in mice in 1994 and reported in July 1995 that it makes leptin, which is produced only in fat and then is released into the blood stream.

The findings reported in the Nature Medicine article stem from studies in people, mice and rats by scientists at Rockefeller, HHMI, Brookwood Biomedical Medical Center, Cedar-Siani Medical Center, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). NIDDK supported the research, along with the U.S. Public Health Service and the American Heart Association.

The research contributes to a growing understanding of the causes of obesity, which affects one in three Americans. Obesity, being more than 20 percent above a healthy weight, is a major risk factorfor diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, stroke, sleep apnea, gallstones, some cancers and forms of arthritis. In the United States, 50 million adults are obese, according to NIDDK.

In the study, investigators found that, in general, the greater the body mass and percent of fat, the higher the levels of leptin. In people, the amount of leptin in blood highly correlated to a person’s percent of body fat and his or her body mass index (BMI), a measurement of kilograms/meter2. However, the leptin level varied greatly from person to person. For example, the amount of leptin for some obese patients with BMIs larger than 40 was the same as for patients with BMIs less than 20.

Women had significantly more leptin than men. However, when compared by percent of body fat, women and men had similar leptin levels. “The greater absolute leptin levels in women reflects that they have higher body fat content than men,” Friedman explains.

In the animal studies, the scientists again found that leptin levels related to BMIs. Specifically, when the researchers compared normal weight mice from the same litters to four kinds of genetically overweight mice, the leptin levels were 10 times greater in diabetic (db) and yellow agouti (Ay) mutant mice, five-fold more in fat mutant mice and twice as high in tubby (tub) mutant mice. Also, three strains of overweight, nonmutant mice had increased leptin levels ranging from 25 to seven times more than littermates. Leptin levels in fatty (fa) mutant rats were 50 times greater than that of non-mutant litter mates.

Dieting decreased leptin levels in the 13 people studied, the scientists report, and, in general, the greater their initial leptin level, the more it declined with dieting. Similarly, in normal mice, leptin levels dropped to 60 percent of the pre-diet amount after a three-day fast and 20 percent after a six-day fast. In dbmice, leptin levels did not drop after 15 days of restricted food, but after 28 days of dieting, the mice had no detectable levels of leptin in their blood, and tests revealed reduced ob gene activity.

Among the 87 lean and obese people in the study, 59 were Americans of different ethnicities and 28 were Pima Indians, a population with high rates of obesity. The people ranged in age from 20 to 65 and included 50 women and 37 men. For two days prior to the study, all participants ate a standardized, 35 percent fat diet that was calorically adjusted to maintain their weight. The Pima Indians received a diet that was 30 percent fat. The 13 dieting participants ate low calorie diets, 520 to 800 calories per day. The investigators measured individual’s leptin levels in blood samples and ob gene activity in fat tissue.

Friedman and Maffei’s coauthors include: Jeffrey L. Halaas, Gwo-Hwa Lee, Ph.D., Yiying Zhang, Ph.D., Hon Fei, Ph.D., and Sharon Kim at Rockefeller; Eric Ravussin, Ph.D., and Richard E. Pratley, M.D., at NIDDK; and Roger L. Lallone, Ph.D., of Brookwood Biomedical in Birmingham, Ala.; and S. Ranganathan, M.D., and Philip Kern, M.D., of Cedar-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, Calif. Lee and Zhang have HHMI appointments.