Rockefeller issues license for the development of novel anti-inflammatory drug

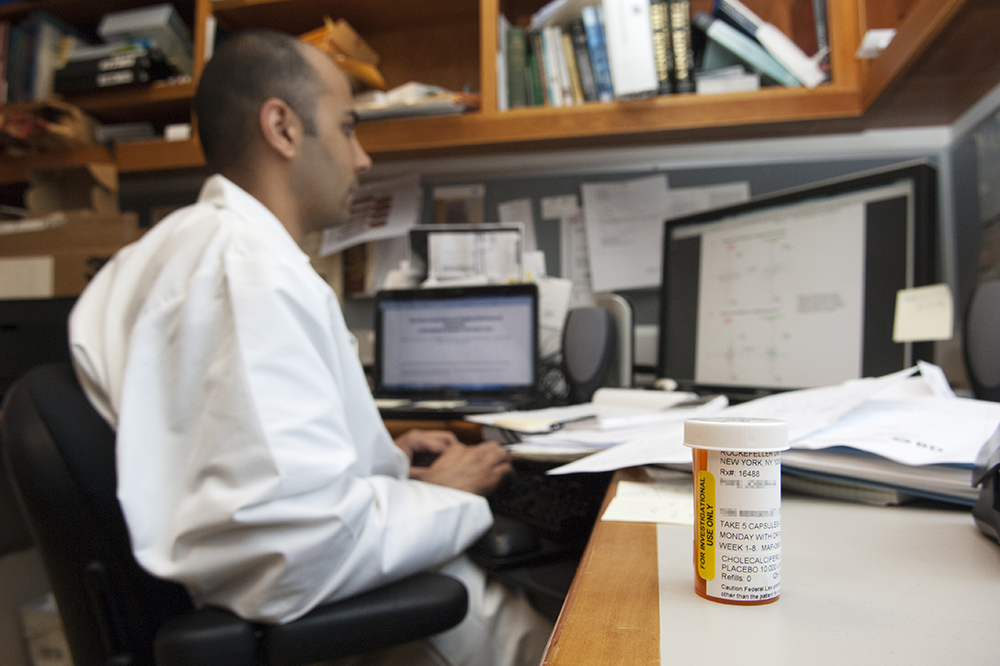

Manish Ponda, in the lab of Jan L. Breslow in 2012. Together, Breslow and Ponda discovered compounds that may help treat immune-mediated conditions.

A series of compounds discovered in the laboratory of Rockefeller’s Jan L. Breslow will be developed into novel medicines, the drug discovery company Bridge Medicines recently announced. These compounds have shown promise in treating immune-mediated conditions in animals, such as models of rheumatoid arthritis, without compromising the immune system and harming the rest of the body—a side effect that, in one form or another, plagues almost every anti-inflammatory drug.

“The pathway that we are targeting only comes to life at sites of inflammation, while the rest of the body’s white blood cells continue surveillance,” Breslow says. “We realized early on that, if we could inhibit this pathway, we could decrease inflammation without untoward side effects.”

The research, initially funded by the Robertson Therapeutic Development Fund, will now be licensed exclusively to Bridge Medicines, where Breslow’s lab will see their small molecule inhibitors develop into novel therapies.

It’s the culmination of work that began almost fifteen years ago when Manish Ponda, a nephrologist, approached Breslow about a confusing trend: patients suffering from both kidney disease and atherosclerosis were responding poorly to cholesterol medications. The scientists designed a series of experiments in mice mimicking the two diseases and determined that part of the problem seemed to be that white blood cells were accumulating abnormally in atherosclerotic lesions. However, they couldn’t figure out what caused this phenomenon—until one otherwise unremarkable experiment stopped them in their tracks. While preparing a routine assay, Breslow and Ponda noticed that one of their serum controls appeared to be speeding up the migration of white blood cells.

Breslow and Ponda immediately realized the significance of this finding. One of the cardinal features of inflammatory disease is the abnormal presence of white blood cells in tissue where they do not belong. Conventional anti-inflammatory drugs work by crippling or killing these cells wherever they are, like a broad brush that paints over the body’s entire immune system. As a result, these medications can leave patients immunosuppressed, heightening their risk of infections and other medical conditions. If there were a substance in blood that could impact only abnormal white blood cell migration, while leaving normal cell activity unharmed, isolating it could be a first step toward designing safer life-saving drugs.

Prospecting for an unknown substance in serum proved challenging, and it was not until late 2013 that Breslow and Ponda finally purified the molecule responsible for the behavior that they had witnessed several years earlier. It was a fragment of kininogen, a group of precursor proteins involved in regulating the cardiovascular and renal systems. And in order to accelerate white blood cell movement this precursor protein required Factor XII, a protein known to play a role in blood clotting but not previously thought to be involved in the body’s immune response.

The rewards were immediate. “As soon as we confirmed that activated Factor XII was required, this unlocked new biomedical understanding,” says Ponda, who is currently with Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. “We demonstrated that, through the kininogen fragment, activated Factor XII could accelerate the movement of a whole range of immune cells, from T cells to dendritic cells and macrophages. This helped solidify a developing narrative in the field that inflammation, coagulation, and immunity have several overlapping pathways in common.”

Crucially, studies had shown that some healthy people do not have Factor XII at all, and do not seem to suffer any adverse effects from the missing protein. “This meant that if we inhibited this factor, negative reactions would be unlikely because people who lack the protein live full, healthy lives,” Breslow says. “It was very fortuitous.”

More fortuitous still, just as Breslow and Ponda were considering what to do with Factor XII, Rockefeller launched the Robertson Therapeutic Development Fund to help scientists translate basic science discoveries into novel medical therapies. Over the next three years, the fund supported the development of a series of Factor XII inhibitors that, once they had been shown to ameliorate inflammatory diseases in animal models, were licensed to Bridge Medicines, which will usher the drugs through the stages of clinical development.

“It’s been a long road,” Breslow says about the project, adding that it was worth the wait. “We think that the compound that we’ve identified is a general inhibitor, which may help treat painful and deadly inflammatory conditions without the rest of the immune system falling apart.”