New approach to treating gastrointestinal disease patches up leaky intestines

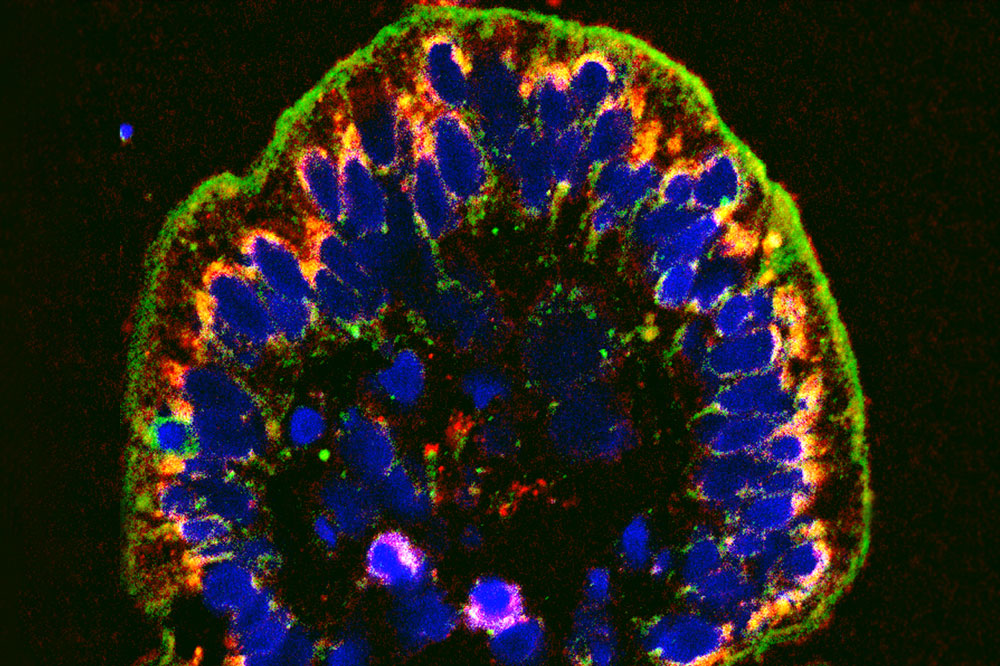

The cellular wall lining the intestine, shown here in green, becomes porous in IBD. A new compound can help seal the leaks.

Doctors typically prescribe anti-inflammatory drugs to people suffering from inflammatory bowel diseases like Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis. These medications, however, leave much to be desired: they are often ineffective and can come with unpleasant side effects. What’s more, they tend to remedy the symptoms of the disease rather than fixing the underlying problem.

Now, a multi-institutional study by Rockefeller scientist W. Vallen Graham and colleagues points to a novel approach to managing IBD. Published in Nature Medicine, the study describes the discovery of a new compound that targets not the inflammation itself, but the leaky intestinal tracts that lead to inflammation in the first place.

Into the intestines

Affecting three million Americans, IBD refers to a number of disorders that involve inflammation at different points along the digestive tract, leading to diarrhea, vomiting, and severe abdominal pain.

One hallmark of the condition is a weak epithelial barrier. The cellular wall lining the intestine becomes porous, causing bacteria and other intestinal contents to leak into surrounding tissues.

This disease feature gave Graham an idea: he set out to identify a molecule that would fortify the intestinal barrier. Specifically, he wanted to find a drug that would halt the activity of a protein called myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), which regulates the seals between cells, called tight junctions.

Targeting MLCK, however, came with its own challenges.

“MLCK has a ton of functions, so nobody had been able to make a drug against it that’s not toxic,” says Graham, who began the research in the lab of Jerrold Turner, Professor of Pathology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, and has continued it as a research associate in the lab of Rockefeller’s Thomas P. Sakmar. “We hit a wall, until we discovered that there’s a variant of MLCK that’s specific to the cells affected by IBD.”

Following this discovery, Graham and his colleagues used computer software to search for compounds whose structure make them likely to glom onto a specific version of MLCK—a form of the protein known to affect tight junctions. Ultimately, they identified a single compound that did the trick and named it Divertin—because it diverts, or redirects, the protein that causes leakiness away from the seals that glue cells together.

“This is exciting because the available medications have certain drawbacks and there’s currently no drug that can remedy permeability of the intestine,” says Graham.

Of the patients taking anti-inflammatories, up to thirty percent don’t respond. Those who are helped by these drugs eventually run into other problems because anti-inflammatories tend to suppress the immune system, which over time may cause a lot of complications.

A molecule like Divertin has the potential to not only to help patients with IBD, but also those with other gastrointestinal disorders where gut leakiness is an issue, like infectious enterocolitis, food allergies, and celiac disease.

Sealing the leak

When the researchers tested Divertin in cell lines and human tissue biopsies it checked off all the boxes for being a promising drug candidate worthy of further exploration. It blocked MLCK from reaching tight junctions, but didn’t disturb the protein’s other functions. It also improved the leakiness of the intestine and reduced IBD symptoms such as diarrhea in mice.

But the homerun of this work, according to Graham, was when he and his colleagues gave mice with IBD an anti-inflammatory and Divertin together. “These mice were better off than they were on either drug alone,” he says. “We think the combination works so well because each drug targets a different part of the system—the anti-inflammatory quiets the immune system while Divertin resolves barrier function.”

While Divertin itself doesn’t fulfill the requirements to move forward to clinical trials in humans—it doesn’t bind tightly enough to its target, for example—it holds great promise for the development of future compounds that act in a similar way. The next step is to redo the search for MLCK-inhibiting molecules using drug discovery technology that has advanced significantly since Divertin was first identified.