Researchers identify gene that calms the mind and improves attention in mice

Key takeaways

- Attention disorders are characterized by poor ability to filter out distractions in a busy world. Current treatments for ADHD work by stimulating brain activity.

- In mice, low Homer1 levels lead to high attention. This happens through increased inhibition, rather than stimulation, allowing for faster and more precise responses to cues, an indication of sharper focus.

- The findings may lead to alternate therapies that calm the mind to improve attention.

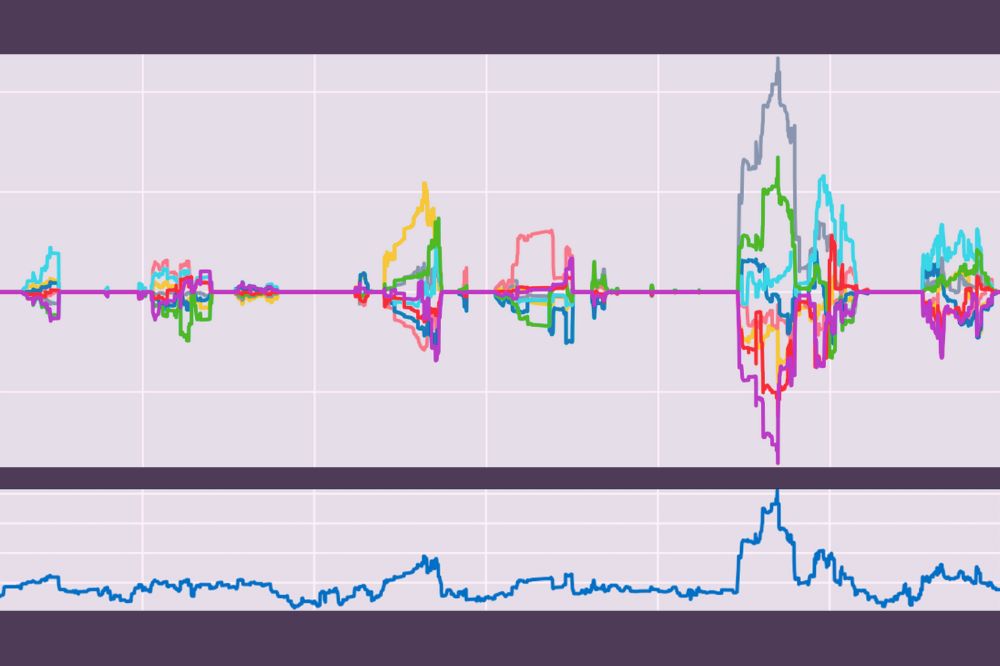

A quantitative trait locus graph showing that the Homer1 gene region is associated with behavioral divergence in attention. (Credit: Rajasethupathy lab)

Attention disorders such as ADHD involve a breakdown in our ability to separate signal from noise. As the brain is constantly bombarded with information, focus depends on its ability to filter out distractions and detect what matters. Currently used stimulant medications improve attention by boosting activity in prefrontal circuits known to govern attention. But a new study suggests an alternative way to improve attention: reduce background activity as a way of turning down extraneous noise.

In a paper published in Nature Neuroscience, researchers show that the Homer1 gene plays a critical role in shaping attention in just that way. Mice with lower levels of two specific versions of the gene enjoyed quieter brain activity and improved ability to focus. The findings may be the first steps toward a novel therapeutic approach to calming the mind, with implications for ADHD as well as related disorders characterized by sensory overload and already linked to Homer1, such as autism and schizophrenia.

“The gene we found has a striking effect on attention and is relevant to humans,” says Priya Rajasethupathy, head of the Skoler Horbach Family Laboratory of Neural Dynamics and Cognition at Rockefeller.

A role for Homer1

When researchers set out to study the genetics of attention, they did not expect to land on Homer1. Though the gene is well known to scientists for its role in neurotransmission—and many interacting proteins of Homer1 have shown up in human genetic studies of attention disorders—there were no previous indications that Homer1 itself might be steering the bus.

The team began by scanning the genomes of nearly 200 mice outbred from eight different parental lines, including some with wild ancestry, to mimic the genetic diversity found in human populations. This unusually broad variation made it possible to spot genetic effects that might otherwise be missed. “It was a Herculean effort, and novel for the field,” says Rajasethupathy, who credits PhD student Zachary Gershon for pulling it off.

Using this approach, they ultimately narrowed in on their observation that high-performing mice had far lower levels of Homer1 in the prefrontal cortex, the brain’s attention hub. This gene was found within a genetic locus that accounted for almost 20 percent of the variation in attention across mice—”a huge effect,” Rajasethupathy says. “We could be overestimating this number due to experimental design, but even accounting for that, this is a sizeable effect.”

Digging deeper, they showed that specifically the versions of Homer1 known as Homer1a and Ania3 were causing the difference. Mice that performed well on attention tasks had naturally lower levels of these shorter versions of the gene, but not any of the other long isoforms of the gene, in their prefrontal cortex. Subsequent experiments showed that dialing down these versions in adolescent mice during a narrow developmental window led to striking improvements. The mice became faster, more accurate, and less distractible across multiple behavioral tests. The same manipulation in adult mice, however, had no effect, demonstrating that Homer1’s influence appears to be locked into a critical early-life period.

The biggest surprise, however, came when the team examined what Homer1 was doing to the brain, mechanistically. They found that reducing Homer1 in prefrontal cortex neurons caused those cells to upregulate GABA receptors—the molecular brakes of the nervous system. This shift created a quieter baseline and more focused bursts of activity when cues appeared: instead of firing indiscriminately, neurons conserved their activity for moments that mattered, enabling more accurate responses.

“We were sure that the more attentive mice would have more activity in the prefrontal cortex, not less,” Rajasethupathy says. “But it made some sense. Attention is, in part, about blocking out the noise.”

A prescription for mindfulness?

The results were less surprising to Gershon, who lives with ADHD himself. “It’s part of my story,” he says, “and one of the inspirations for me wanting to apply genetic mapping to attention.”

Gershon was actually the first in the lab to notice that reducing Homer1 was improving focus by reducing distractions. To him, it made perfect sense. “Deep breathing, mindfulness, meditation, calming the nervous system—people consistently report better focus following these activities,” he says.

Existing therapies for attention disorders amplify excitatory signals in prefrontal circuits with stimulant medications. But these new findings point toward a potential pathway for a novel kind of ADHD medication that could calm rather than stimulate. And the fact that previous studies have linked Homer1’s interacting proteins to ADHD, schizophrenia, and autism suggests that further study of this gene may provide new frameworks for thinking about a number of neurodevelopmental disorders that all involve sensory overload.

Future work from the Rajasethupathy lab will endeavor to better understand the genetics of attention, with an eye toward therapies that could result in precise molecular targeting of Homer1 levels.

“There is a splice site in Homer1 that can be pharmacologically targeted, which may be an ideal way to help dial the knob on brain signal-to-noise levels,” Rajasethupathy says. “This offers a tantalizing path toward creating a medication that has a similar quieting effect as meditation.”