Watching fruit fly larvae crawl towards odors provides clues to how smells are detected

In an effort to understand how smells influence behavior, Leslie Vosshall has been watching fly larvae inch their way across Petri dishes. It may not be high-tech, but this technique has been helping scientists study neurobiology for the past 20 years. And a refinement of it, in which the larvae’s movements are recorded and analyzed statistically, is now leading Vosshall and her colleagues to new understandings about how animals use multiple brain cells to process what they smell.

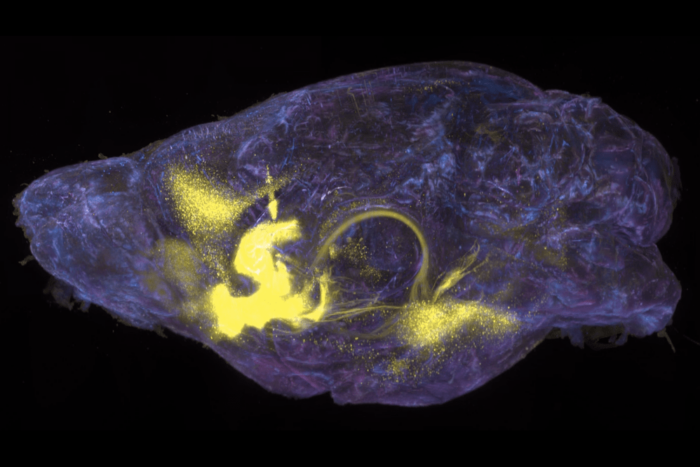

“The anatomy of the fruit fly olfactory system is similar to the human and mouse systems,” says Vosshall. “Though larvae are much simpler—they have only 21 olfactory sensory neurons and about 25 odorant receptor genes. These are very manageable numbers and we can completely manipulate the biology of this animal to dissect how they detect odors.”

In work pioneered by two graduate students in her lab, Elane Fishilevich and Ana Domingos, a system was created in which olfactory neurons could either be shut off one at a time, or shut down all together, then single neurons added back. The contributions of each neuron to a larva’s ability to detect odor were measured based on the larva’s movement towards an odor source.

“You can’t ask the larvae ‘are you smelling or not smelling,’” says Vosshall. “But you can watch them crawl on a plate and, through some sophisticated statistics, determine if they are detecting an odor or not.”

What Vosshall and colleagues found was that there is that the different neurons and receptors have some overlap in the odors that they can detect. Taking away single neurons did not affect the animals in major ways, and adding back specific neurons could restore much of a larva’s sense of smell. And while certain neurons on their own could not help the animals detect smell, in some cases they did enhance odor detection in combination with one or two others. The results suggest that a combinatorial code is key to the animal’s ability to recognize specific odors.

“What we found about the olfactory system is that when it comes to odor detection, the sensory system is greater than the sum of its parts,” says Vosshall.