Identification of carbon dioxide detectors in insects may help fight infectious disease

Mosquitoes don’t mind morning breath. They use the carbon dioxide people exhale as a way to identify a potential food source. But when they bite, they can pass on a number of dangerous infectious diseases, such as malaria, yellow fever, and West Nile encephalitis. Now, Leslie Vosshall’s laboratory at Rockefeller University has identified the two molecular receptors in fruit flies that help these insects detect carbon dioxide, which could prove to be important against the fight against global infectious disease.

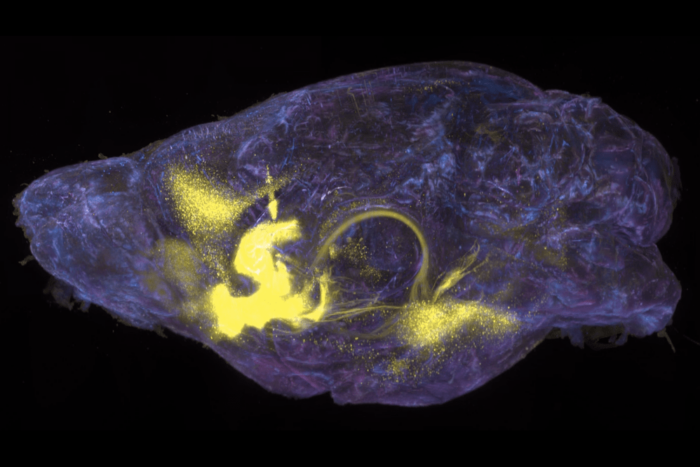

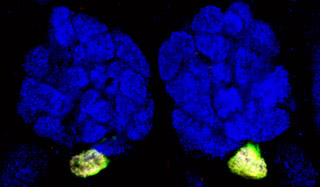

Nerve gas. In a fly’s brain (blue), highlighted areas show where neurons expressing two proteins, Gr21a and Gr63a, converge. Scientists have shown that these proteins are necessary in order for the fly to detect carbon dioxide.

“Insects are especially sensitive to carbon dioxide, using it to track food sources and assess their surrounding environment,” says Vosshall, head of the Laboratory of Neurogenetics and Behavior and the Chemers Family Associate Professor. “The neurons in insects that respond to carbon dioxide were already known, but the molecular mechanism by which these neurons sense this gas was a mystery.”

One protein, called Gr21a, was previously known to be expressed in the carbon dioxide-responsive neurons, which are in the antennae of the fruit fly. Since in the fly, chemosensory receptors usually work together as a pair of unrelated proteins, Walton Jones, a former biomedical fellow and first author of the paper, began by looking for other members of the gustatory receptor family, and found that the Gr63a protein was always co-expressed with Gr21a, both in the larva and in the adult fly.

“I went on to look at the malaria mosquito and found two homologues of the fly genes, GPRGR22 and GPRGR24. They are also co-expressed in the mosquito’s maxillary palp, the appendage mosquitoes use to sense carbon dioxide,” says Jones.

Using genetic manipulation, Jones was able to show that both Gr21a and Gr63a are all that is needed for a fly neuron to sense carbon dioxide. He took neurons that did not normally respond to carbon dioxide and found that only if he expressed both Gr21a and Gr63a together, those neurons became excited by the gas. He also showed that when Gr63a is mutated, the mutant flies no longer respond to the high levels of carbon dioxide that wild type flies avoid.

These molecules are the first membrane-associated proteins that have been shown to sense a gas. All previously described gas sensors have been cytoplasmic. “Though we don’t know what other proteins might be involved in the signaling pathway, the identification of the carbon dioxide receptor provides a potential target for the design of inhibitors that would act as an insect repellent,” says Vosshall. “These inhibitors would help fight global infectious disease by reducing the attraction of blood-feeding insects to humans.”