Rockefeller scientists tell their stories in new oral history project

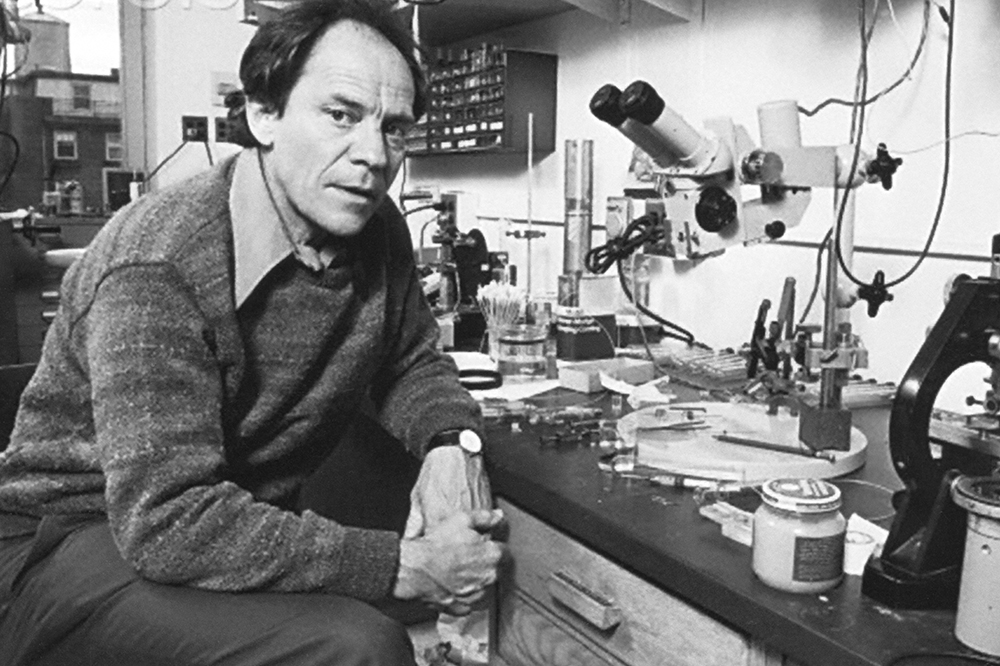

Torsten Wiesel in his lab, 1981.

There are fascinating aspects of scientific research that you will never read about in academic journals. Peer reviewers may be tireless in asking authors to provide more data points, but they don’t typically invite comments on the thrill that accompanies discovery, or the frustration of failed experiments. And rarely do methods sections reveal crucial friendships formed over the course of a career, or the personality quirks of a particular researcher.

Filling in these gaps, two years ago Rockefeller launched an oral history project that injects a dose of humanity into the university’s rich record of scientific achievement. Now, the early fruits of this ongoing endeavor are available online.

Currently, the project’s website features mini-documentaries about the lives and work of Günter Blobel, James E. Darnell, Paul Greengard, Torsten N. Wiesel, and Michael W. Young. Videos about Mary Jeanne Kreek and Bruce S. McEwen are in the works, and installments featuring other Rockefeller scientists will be added in the coming years. Produced by oral historian Leyla Vural, the videos delve into everything from the subjects’ childhoods to their personal philosophies—all in about ten minutes.

These short films result from a much deeper process, however: Vural interviewed each scientist on camera for over four hours. The unabridged videos, audio files, and transcripts will be kept in Rockefeller’s on-campus library, and eventually in its archives in Tarrytown, New York. This developing resource, says Vural, can be highly valuable to historians, scientists, and other researchers.

“If someone wants to understand the history of a specific field of knowledge, or of a scientist, these interviews can provide information that doesn’t exist anywhere else,” she says. “For instance, Günter Blobel describes his research with wonderful richness and a textured detail—I think that’s really important knowledge to preserve.”

Its historical value notwithstanding, the project is not a purely academic pursuit. The online videos are intended to appeal to a wide audience, ranging from current Rockefeller staff to viewers who have never stepped foot on campus, or in any lab for that matter.

“People who don’t work in science might not fully be aware of the human aspects of the research process,” says Franklin Hoke, associate vice president of Communications and Public Affairs. “And these histories can provide a window into the powerful curiosity that drives scientists and the excitement behind discovery.”

Independently from the oral history project, the Rockefeller library has undertaken a different project to collect commentary from a broad range of community members, available in the library’s digital archive.

Fascinating and frequently touching, the oral history videos bring to light the sometimes-suprising circumstances that nudge a scientist in one direction or another. For instance, Greengard describes in his interview the moment that he transitioned out of physics and into biology.

“The only money available in physics at that time was atomic energy commission fellowships—and this is three years after we dropped the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” he recalls. “I thought, I don’t want to use whatever talent I might have to develop better nuclear weapons. So I looked around for another thing.”

That search for “another thing” ultimately led Greengard to make groundbreaking discoveries about how cells in the brain exchange messages.

Stories like Greengard’s, it turns out, are not rare. Blending triumphs and tribulations, reason and emotion, the oral history project highlights the ways in which science—and scientists—are entangled with the rest of society.

“Rockefeller scientists are making history every day,” says Hoke. “We owe it to ourselves as an institution—but also to the rest of the world—to capture that history as fully as we can and to share it.”