Joseph M. Luna

Joseph M. Luna

Joseph M. Luna

Presented by Robert B. Darnell on behalf of himself and Charles M. Rice

B.S., Yale University

A Genomic Portrait of Hepatitis C Virus and MicroRNA-122

“The crowded hall was brimming with excitement as a room full of scientists took their seats.” These prescient words were written by Joe in his application to Rockefeller University. They capture his excitement at and investment in science and the scientific community, and happily, they presaged Joe’s spectacular thesis talk given here this spring. Before I tell you about what he has accomplished at Rockefeller, it is worth noting how his own background lay the groundwork for his success here.

Joe came from El Paso, Texas, where he was raised by a wonderful, energetic, and forward-thinking family that I have had the privilege of coming to know. This led him on a path of intellectual curiosity—he took on the very challenging molecular biophysics and biochemistry major as an undergraduate at Yale, while at the same time becoming literally a master printer—he was the chief printer to Jonathan Edwards College. This may seem like a stretch, but I believe Joe saw this as a physical incarnation of the very concept of scholarship—how does one make books (knowledge) from lead and brass? He has since applied this analogy to the experiments and advancement of science.

At Rockefeller, Joe became fascinated by the relationship of microbial-host interactions, and how it leads to the “accident” of disease. This attracted him to a number of microbiology projects at Rockefeller, and he eventually settled on studying hepatitis C with Charles Rice’s Laboratory of Virology and Infectious Disease. At the same time, Joe was interested in the “lead and brass” of molecular biology, and decided on developing a joint program with dual thesis advisors, Charlie and me.

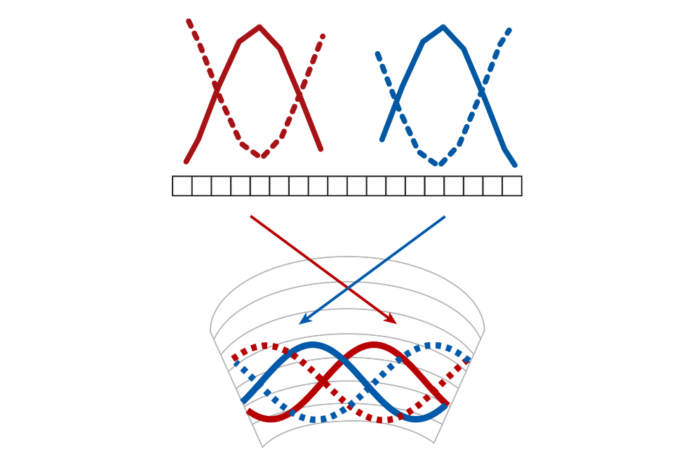

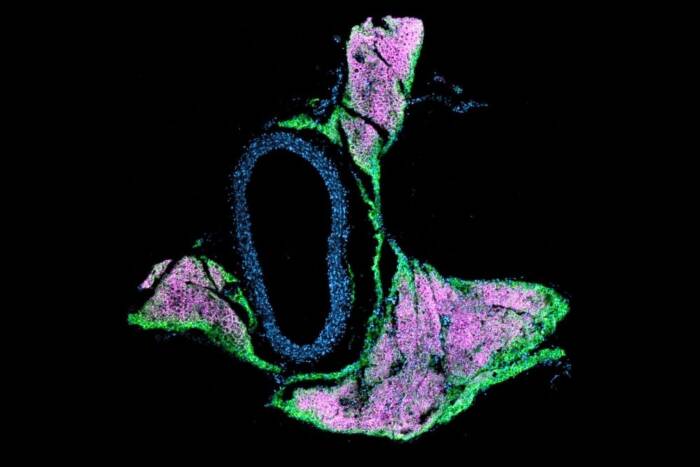

As I noted early in his Rockefeller career, when Joe received the David Rockefeller Fellowship, Joe was “as fully engaged as one could possibly hope for from a young scientist.” Joe took a technique that our lab had developed, termed HITS-CLIP, in which one can very precisely lock RNA molecules inside living cells to the proteins that regulate them, and applied it for the first time to understand host-viral interactions. Joe’s work, reviewed by a panel of virologists at his thesis defense, was stunning in its careful execution and precision, confirming and extending our understanding of the basic molecular biology of how hepatitis works, focusing on how regulation of the viral RNA at one end is addicted to a single small host microRNA, termed miR-122.

Joe took this understanding to a new level, reasoning that the virus, in its addiction to the liver cell’s own miR-122, exposes a potentially very important Achilles’ heel. That is, by “sponging up” all of the host liver cells’ miR-122, it leaves the normal mRNAs that are normally controlled by miR-122 freed from their normal regulatory constraints. This observation has potentially great relevance for understanding hepatitis C. Nearly 200 million people are infected with the virus, with outcomes ranging from “no-problem” to chronic infection with its complications, including, in a not insignificant number, the development of liver cancer. While the virus appears the same in each patient cohort, Joe’s discovery of a new set of virus-host interactions has great importance for understanding why some get so sick from this virus. Joe’s work has impressed many beyond those who have worked so happily and so closely with him—it was published last month in Cell with Joe as the first author, a major work attracting interest from virologists, cancer biologists, and molecular biologists. Charlie and I both feel privileged to have worked with Joe, and will support him as strongly as we can as he goes forth into the world of science.