Eliot Dow

Eliot Dow

Eliot Dow

Presented by A. James Hudspeth

B.S., Ohio State University

Synapse Formation in the Zebrafish Lateral Line

Although our brains do not always function well, it is actually implausible that they should function at all. A human brain contains something like a hundred billion nerve cells, but the instructions for assembling that organ—not to mention the remainder of the body—reside in just twenty thousand genes. A central problem in neuroscience is therefore how development can erect an edifice as complex as the brain from such a scanty blueprint.

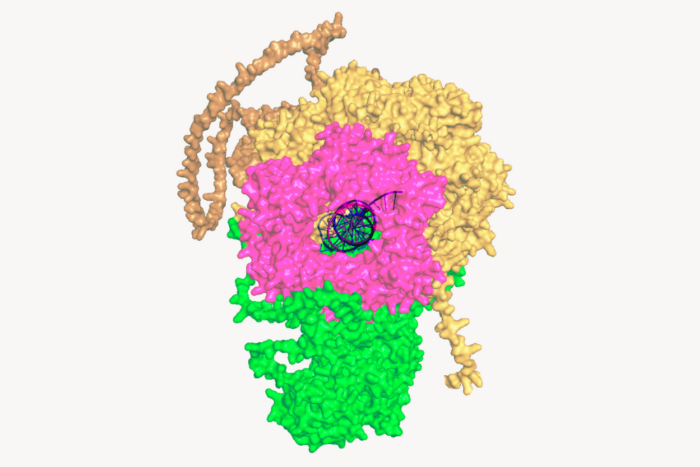

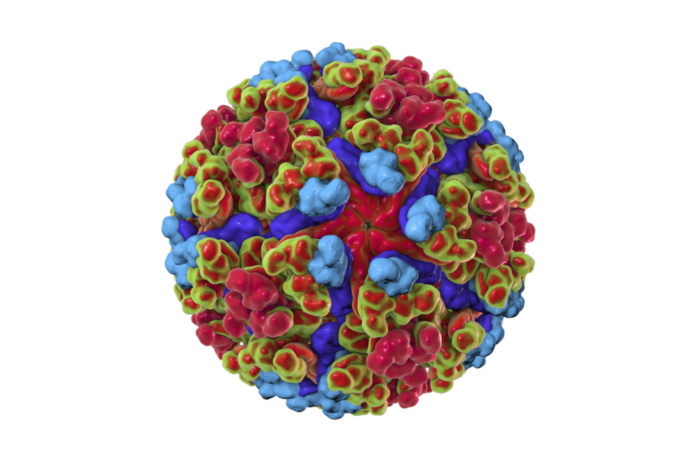

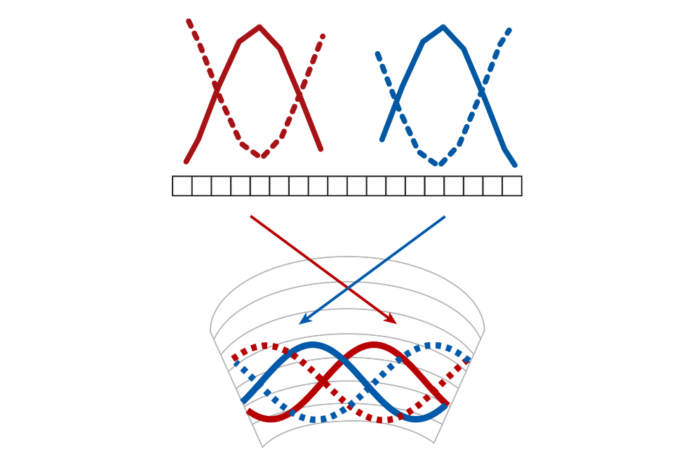

Eliot Dow has contributed to an understanding of this issue by conducting research on an experimental system meant to display a minimum of complexity. As you can verify from the next trout that you encounter, a fish has a prominent stripe along its side. This lateral line contains cells that detect water motion, informing the fish how fast it is moving and signaling the approach of predators or prey. The simplicity of the system resides in the fact that water moves either fore or aft along the fish, and there are separate cells that detect the two. Moreover, those cells are connected to just two classes of nerve cells, again with opposite sensitivities. An investigator can therefore ask how nerve cells connect when they have only two choices—right or wrong—rather than thousands or even millions of options. Eliot used this system to discover a novel phenomenon: the sensory receptors do not passively await contact with the appropriate nerve fibers; instead, they extend microscopic arms and essentially grab the proper nerves. This observation has sparked an entirely new line of investigation into the formation of nerve connections.

Although Eliot worked with extraordinary vigor and perseverance on his doctoral research, he also found a potent means of amplifying his effort. Defining the elaborate connections between nerve cells requires laboriously tracking each cell through hundreds of tissue slices; a view of the cell then emerges as in an old-fashioned flip book. Reasoning that New York City is full of starving artists, Eliot advertised on Craigslist for individuals with appropriate graphical skills and computer facilities. The response was gratifying: there are a lot of people hereabouts who are interested in science, but not fortunate enough to have academic careers. Knowing that they could make a genuine contribution to human knowledge—and get paid for it—these individuals were eager to participate in research and did an outstanding job of identifying the various cells in Eliot’s preparations.

As a student in the M.D.-Ph.D. program, Eliot recently returned for his final two years of clinical education. It remains to be seen what will transpire thereafter, but I must admit a prejudice: Eliot has an exceptional gift for research, and I hope that he will use it to learn more about how the brain is assembled.