Chiung-Ying Chang

Chiung-Ying Chang

Chiung-Ying Chang

Presented by Elaine Fuchs

B.S., M.S., National Taiwan University

Coordinating Stem Cell Behavior in the Hair Follicle

Chiung-Ying Chang received her bachelor and master of science degrees from National Taiwan University. She joined my laboratory in summer 2009, after completing her rotations and her first year in our graduate program. I was delighted that she chose my lab, as she is a careful experimentalist and is able to think through scientific problems, devise and perform experiments for testing her hypotheses and interpret her results with accuracy.

Chiung-Ying’s graduate project centered on defining the role of transcription factor Nuclear Factor I B (NFIB) in mouse skin development. This transcription factor had initially surfaced as being more abundant in hair follicle stem cells than other cells of the skin. Little else was known about this factor, except that it is found in a number of tissues of our body.

Chiung-Ying used mouse genetics to engineer a null mutation specifically in the hair follicle stem cells of laboratory mice. At first she was disappointed in that the mice were viable and grew a seemingly normal hair coat. As the mice grew, however, their ears started to become black. For me this was exciting as I grew up watching the Mickey Mouse Club show. Chiung-Ying took wiser joy in sleuthing the underlying reason.

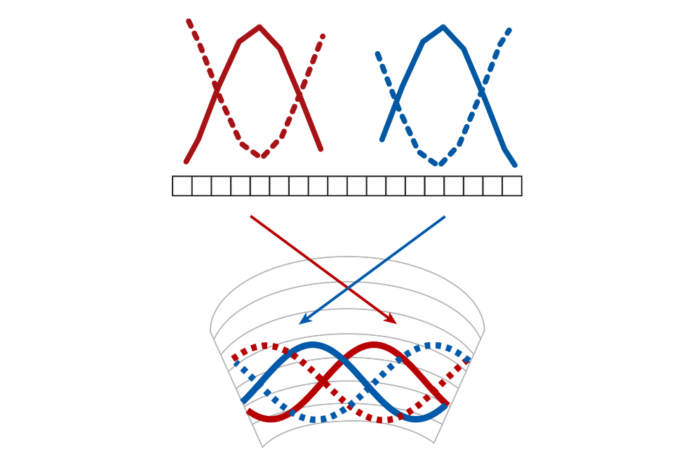

I won’t elaborate on the details, which were published in Nature, but Chiung-Ying had inadvertently uncoupled the normal crosstalk that takes place in the hair follicle stem cell niche that allows the melanocyte stem cells and the hair follicle stem cells to become activated and differentiate at the same time, so that differentiating melanocytes can deliver melanin to differentiating hair cells so that your hairs are pigmented. NFIB turned out to repress a gene in hair follicle stem cells that encodes a secreted melanocyte differentiating factor. To get to the bottom of the story necessitated complex mouse genetics, cell and developmental biology approaches, in vivo chromatin immunoprecipitation and deep sequencing, RNA-sequencing and functional analyses.

What I particularly liked about Chiung-Ying’s work is that many would have overlooked the phenotype and turned to another project (particularly if they did not grow up learning about Mickey Mouse). Chiung-Ying pays attention to details, she tackles problems head on and has the dedication and persistence to stick with an interesting scientific problem until she gets to the bottom of the story. This kind of strategy often pays off, but so very few have the motivation, patience and conviction to take this approach at such a young age.

Throughout her studies in my laboratory, Chiung-Ying showed a high level of enthusiasm and took a genuine interest in her science. It was Chiung-Ying’s insight and observation that led to her exciting thesis, and she’s developed into a fine and confident young scientist. She’s now in the laboratory of Gerald Crabtree at Stanford, where she’s learning the hard-core transcriptional biochemistry to round out her skills gained in my lab. She’s back today to receive her diploma, and I look forward to watching her progress on the other side of the U.S.