Neel Shah

Neel Shah

Neel Shah

Presented by Tom Muir

B.S., New York University

Split Inteins: From Mechanistic Studies to Novel Protein

Engineering Technologies

Neel Shah joined the Rockefeller graduate program in the fall of 2008 following undergraduate studies at NYU where he graduated with top honors in chemistry. Neel acquired a taste for two things during his years in Washington Square: firstly, protein chemistry, which ultimately led him to my lab, and secondly, insanely hot kebabs which ultimately led me to Prilosec.

Neel was an outstanding student, incredibly productive and an intellectual leader in the group. Although having no prior exposure to the world of the illusionist, Neel nonetheless became fascinated by the art of the escape artist. His “Harry Houdini” was not a man in a straightjacket but a protein called an intein precariously lodged in another protein. Like Houdini, inteins are consummate escape artists, being able to vanish from their immediate surroundings, in this case a protein host. Neel was driven to understand their secrets.

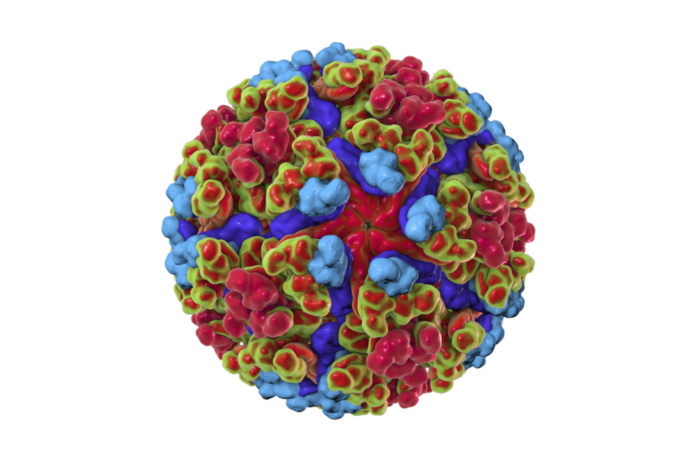

Now my lab has worked with inteins for years and we thought we knew all their tricks. Neel thought otherwise. Using a combination of informatics and cell based screens, Neel discovered a family of inteins that were not only split in half — two separate pieces — but that came together and then “escaped” in a matter of a few seconds; as far as I know, Houdini never pulled that off! The identification of these new ultrafast split inteins — so called because they escape several orders of magnitude faster than anything we had seen before — has been something of a watershed for my lab and beyond, enabling experiments that were impossible even a few short years ago when I was still in New York.

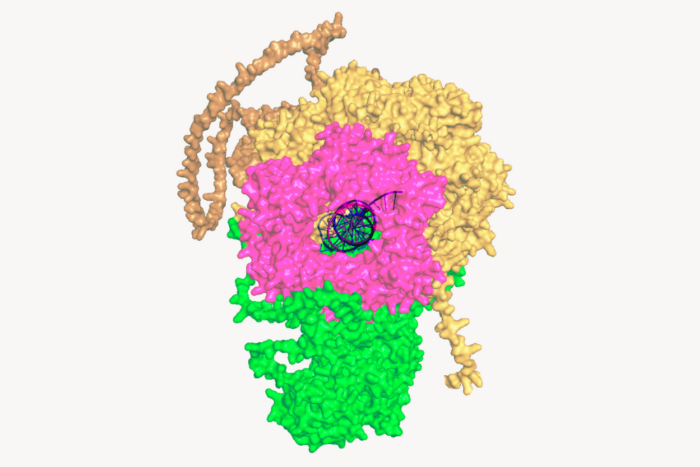

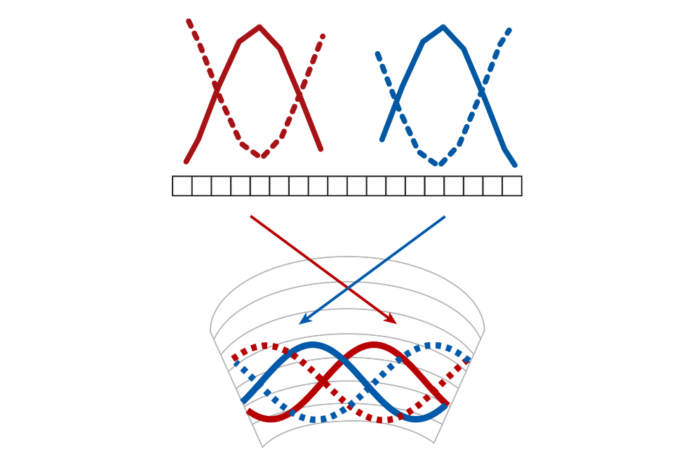

Following this initial discovery, Neel went on make many important contributions to the functional analysis and applications of his ultrafast split inteins — there have been lots of papers. My favorite relates to his work on the initial association of the intein fragments. Remarkably, the two polypeptides become topologically entwined in the final folded complex, forming a knot. Using a battery of methods, Neel figured out how they do this, elucidating the graceful molecular dance that allows the largely disordered intein fragments to capture each other and then, through a kind of adagio movement, fold into the final knot. Unlike Houdini, split inteins actually tie themselves up before escaping.

As alluded to, Neel has left quite an amazingly legacy in my group with many new projects and even a start-up company emerging from his thesis work. But, he also has left another, altogether darker, or at least enduring, legacy. As some of you know, I left Rockefeller a few years ago. What you certainly don’t know is the real reason why, which brings me back to those caustic kebabs. In the end, my GI track could no longer handle the increasingly frequent Shah-led group trips to Mamoun’s Kebab House in the West Village. I simply had to put some distance between myself and Mamoun’s. Neel is now out at UC Berkeley where he is a Damon Runyon postdoc in John Kuriyan’s lab — apparently he has a thing for ex-Rockefeller scientists.