IT amps up bandwidth, eases genomic data transfers

by LESLIE CHURCH

For labs on campus that sequence genomes — and share those large data sets with other institutions — a recent quadrupling in internet bandwidth means an end to the practice of slowing down uploads or scheduling them during overnight hours. In April the university upgraded its internet connection to two gigabits per second for both incoming and outgoing traffic. The new higher speed is approximately 130 times faster than a typical residential broadband connection.

“In recent months we began seeing these big transfers going on during the day, and they had the potential to slow down connections for the rest of campus,” says Jerry Latter, associate vice president of IT and the university’s chief information officer. “We had to start asking labs if they could perform large data transfers on nights and weekends, or throttle their transfer speeds. We weren’t completely maxing out our bandwidth, but it was close enough that we were getting nervous about it.”

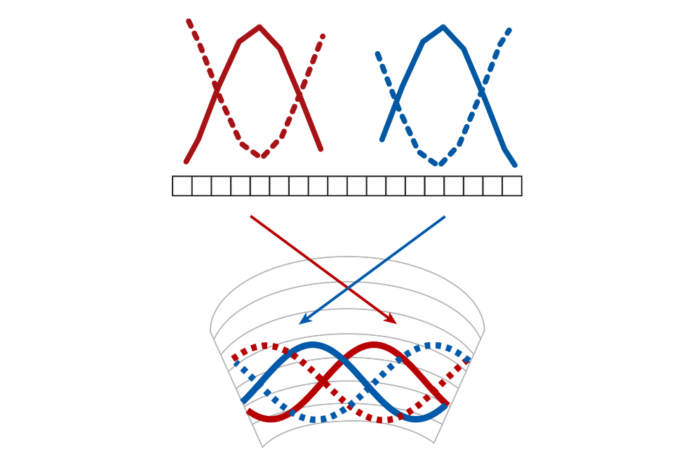

One day’s data. A graph of a typical day’s internet traffic, as metered by IT’s systems, shows the ebb of flow of data during business hours. A pronounced spike between 2 and 4 p.m. was likely a large set of data being retrieved.

For large customers like universities, internet service providers sell connections in a wide range of bandwidths. In recent years the university’s connection was capable of transferring 300 megabits per second, meaning one user could upload or download 300 megabits — equivalent to 30,000 pages of plain text — every second, or 300 users could each transfer one megabit per second. Although fine for general internet usage such as browsing the web or streaming video, this level of service could not easily accommodate large data transfers.

IT, which keeps careful track of internet consumption, notes that usage typically peaks around lunchtime and tapers off after 5 p.m. But with technologies such as high throughput sequencing, which generate data files as large as two terabytes, IT started seeing sharp spikes whenever these files were retrieved or shared.

“The nature of the science is changing,” says Mr. Latter. “There is more sharing of data between institutions and more sequencing being done off-site at places like the New York Genome Center. The need to get large amounts of data on and off campus is greater.”

Rockefeller’s bandwidth has come a long way since the dial-up era of the 1980s, when the university’s T1 connection offering 1.5 megabits per second was considered cutting-edge. In 2002, average usage was just under 10 megabits per second.

Looking forward, the university is poised to continue to expand bandwidth as needed, thanks to its membership in a network-sharing consortium of academic institutions in the state and city. The New York State Education and Research Network (NYSERNet) is a private nonprofit that was founded in 1985 as a way for New York’s academic institutions to tap into a high-speed network. NYSERNet maintains a city-wide network of “dark” fiber that links its institutional members and connects them to a communications hub in downtown Manhattan.

“Dark fiber means that it’s only being used by these institutions, which have the option to turn it on when they need it,” says Mr. Latter. “We pay for the dark fiber at a fixed price from NYSERNet, so we’re able to increase bandwidth as our needs change, at a minimal cost.”