Ted Scovell named new director of Science Outreach

by TALLEY HENNING BROWN

Textbooks and Wikipedia are fine for facts, but to really learn science, you need access to a lab. In his new position as director of Rockefeller University’s Science Outreach Program, Ted Scovell, a former high school teacher himself, hopes to give new generations of young scientists access to the facilities — and mentors — that can take them well beyond dissecting frogs and earthworms. A Harvard University biology graduate and Rockefeller Outreach alumnus himself, Mr. Scovell joined the university February 1. He succeeds Bonnie Kaiser, who retired from the university last year.

Though armed with an impressive science pedigree — as an undergraduate at Harvard University he studied ants with Edward O. Wilson in the 1980s — Mr. Scovell didn’t initially go into science or teaching. Noticing that even the graduate students around him had a hard time finding jobs in science, he opted instead to join the growing field of investment banking. After 11 years as a portfolio and hedge fund manager at big-name firms including Morgan Stanley, First Boston and J.P. Morgan, Mr. Scovell and his wife took a sabbatical in Costa Rica in 1996. Mr. Scovell had his first taste of teaching when he was asked to take over for the injured science teacher in the town of Monteverde. “After that experience, I just couldn’t go back to my old job,” says Mr. Scovell, who the following year took a teaching job at Friends Seminary in Manhattan, where he stayed for the next 12 years.

Though armed with an impressive science pedigree — as an undergraduate at Harvard University he studied ants with Edward O. Wilson in the 1980s — Mr. Scovell didn’t initially go into science or teaching. Noticing that even the graduate students around him had a hard time finding jobs in science, he opted instead to join the growing field of investment banking. After 11 years as a portfolio and hedge fund manager at big-name firms including Morgan Stanley, First Boston and J.P. Morgan, Mr. Scovell and his wife took a sabbatical in Costa Rica in 1996. Mr. Scovell had his first taste of teaching when he was asked to take over for the injured science teacher in the town of Monteverde. “After that experience, I just couldn’t go back to my old job,” says Mr. Scovell, who the following year took a teaching job at Friends Seminary in Manhattan, where he stayed for the next 12 years.

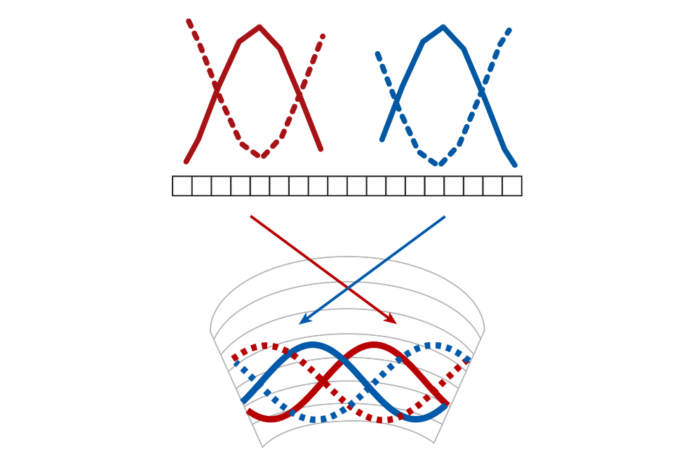

Rockefeller’s Science Outreach Program introduces academically promising high school students, as well as K–12 teachers, to the rigors of basic research by matching them with laboratories and mentors for two summers. Founded in 1992, the program has graduated 761 students and 101 teachers, and an estimated 10 percent of students go on to place in the Intel Science Talent Search and other prestigious science fairs. Mr. Scovell’s Outreach experience, which occurred when he was still fairly green as a teacher in 2000, was in the lab of Richard and Jeanne Fisher Professor Michael W. Young, where he studied the genetic basis of circadian rhythms in fruit flies. The next summer he was paired with Donald W. Pfaff, in whose lab he used oxytocin knockout mice to study the effects of hormones on behavior.

“Ted has been on both sides of the equation, as a teacher and as a student of the scientific process,” says Sidney Strickland, vice president for educational affairs and dean of graduate and postgraduate studies. “Both experiences inform his approach to science education in a way that will greatly benefit the Outreach Program.”

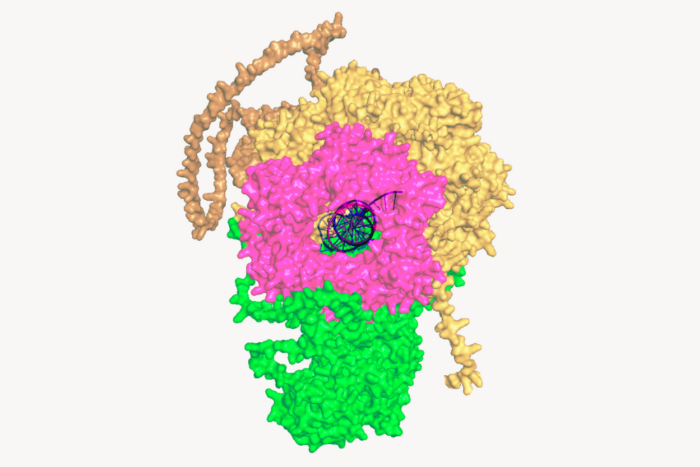

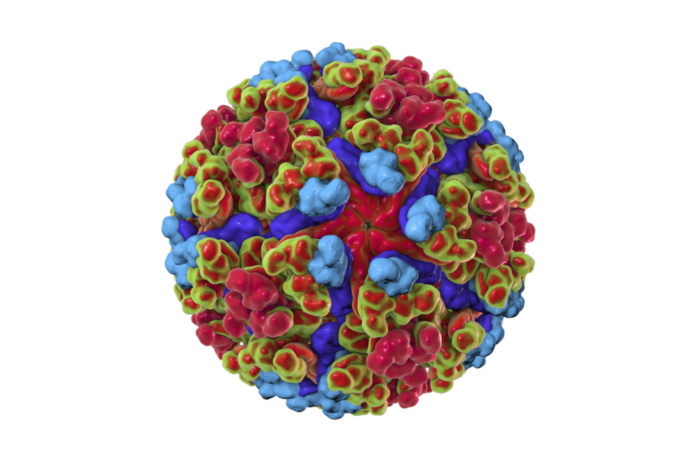

Since 2005, Science Outreach and Rockefeller investigators have also played host to teams of area middle and high school students through the Milwaukee School of Engineering’s SMART (Students Modeling a Research Topic) program. Mr. Scovell, who was trained in the SMART curriculum — using three-dimensional protein modeling to teach the intricacies of chemistry and biochemistry — has himself fielded several SMART teams and will harness Science Outreach to bring SMART teacher training workshops to New York (see “SMART program for teens opens New York branch at Rockefeller,” below).

Mr. Scovell has vetted applications for this summer’s Outreach program and is formulating his plans to reshape its scope. Among other initiatives, he plans to introduce a critiquing component to the mandatory STRAW (Scientific Reading and Writing) course; he will designate second-year Outreach students and teachers as mentors for first-years; he will schedule regular sessions for Outreach teachers to share with each other techniques that have worked or not worked for them; and he is also considering ways to devote some time early in the summer for students and teachers to learn basic lab skills as a group. “It can be scary when you go into a lab for the first time and someone hands you a pipette and you don’t know what to do with it, or you spend the first week stabbing gels and generally feeling clumsy and awkward,” says Mr. Scovell. “By learning these basic skills together as a group beforehand, the students can feel more confident when they split off to join their individual labs. It will also help provide more of a sense of community from which they can draw support, to share the joys and frustrations of the scientific enterprise from their own perspective.”

SMART program for teens opens New York branch at Rockefeller

by Talley Henning Brown

A program to get middle and high school students involved in protein modeling, that began as a regional science education initiative at the Milwaukee School of Engineering and came to Rockefeller University in 2008, will soon have a center of operations in New York City. In line with Ted Scovell’s new position as director of Rockefeller’s Science Outreach Program (see “Ted Scovell named new director of Science Outreach,” above), Mr. Scovell is also launching RU SMART, the New York branch of the original program.

A program to get middle and high school students involved in protein modeling, that began as a regional science education initiative at the Milwaukee School of Engineering and came to Rockefeller University in 2008, will soon have a center of operations in New York City. In line with Ted Scovell’s new position as director of Rockefeller’s Science Outreach Program (see “Ted Scovell named new director of Science Outreach,” above), Mr. Scovell is also launching RU SMART, the New York branch of the original program.

Designed with the double purpose of reinvigorating old-school, often uninspiring science lessons and helping arm future scientists with a deeper knowledge base, the Students Modeling a Research Topic (SMART) program offers workshops to K–12 science teachers on how to incorporate hands-on, three-dimensional molecular modeling into their curricula. Wielding the new method, teachers then partner with professional research scientists to help their students learn more about — and model — a pet protein.

The students in a SMART team spend several weeks with a computer program that allows them to build the protein atom-by-atom, while learning from their scientist-mentor the effect each addition has and the various ways that atoms can form bonds. “By the time they’ve finished building their molecule, they can tell you exactly what its function is and how its structure relates to its function,” says Mr. Scovell. “And they’re excited to share that knowledge.” SMART teams that have partnered with Rockefeller labs have modeled, for example, the bacterial RNA polymerase elongation complex, which is central to bacterial DNA transcription, and the platelet integrin receptor αIIbβ3, which enables blood clotting.

RU SMART, which received $25,000 from a pilot project grant from The Rockefeller University Hospital’s Center for Clinical and Translational Science, kicked off its inaugural season earlier this month with a symposium for New York City’s three 2010 SMART teams: one from The Dalton School, working with a lab at Mount Sinai Medical School; a team from Hostos-Lincoln Academy of Science, working with the Weizmann Institute of Science; and one from Manhattan Hunter Science High School, working with a lab at Hunter College. Each team gave a 10-minute presentation of its work, and there was a poster session with other participating schools in the area. Seth A. Darst, head of the Laboratory of Molecular Biophysics and a host of two SMART teams so far, gave the symposium’s keynote speech. Following in early July, Rockefeller will play host to “Modeling the Molecular World,” a four-day workshop for 12 New York-area K–12 teachers to learn the SMART method for chemistry and biochemistry curricula.

“This method of teaching is still relatively new in schools, but teachers love it. The program has spread even among schools with underprivileged students, and I know from experience that there are some real diamonds in the rough out there, kids who really should be doing research but who might not otherwise have the opportunity,” says Mr. Scovell. “And if we’re training 12 teachers every summer, that will help us build up our contacts at many different schools across the metro area, in turn broadening our recruitment base for the Outreach Program.”