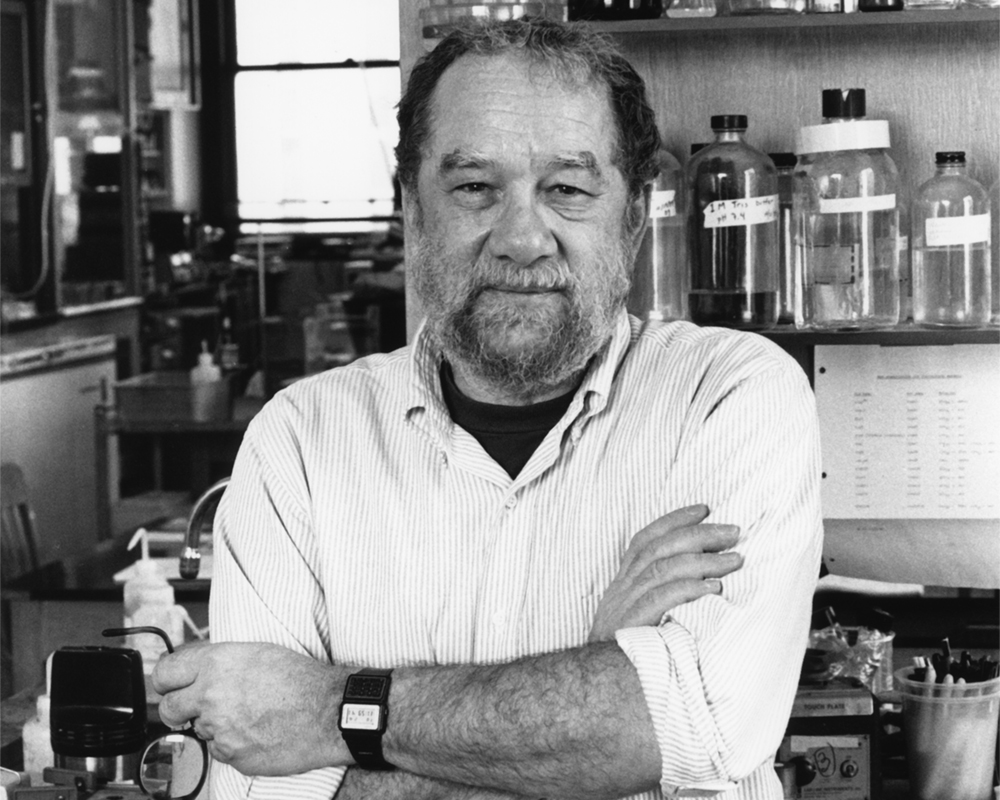

Geneticist and Rockefeller emeritus Peter Model dies at 84

A champion of modern molecular genetics, Model asked questions that changed the way research was conducted. (Photo by Ingbert Grüttner, 1988)

Peter Model, an emeritus faculty member who spent the major part of his career at The Rockefeller University, died on June 9 at the age of 84, after a brief period of declining health. Model used genetics, biochemistry, and molecular biology to study the f1 phage, a type of virus that infects Escherichia coli bacteria. His work provided valuable details about the way genes express themselves and control one another.

“Peter brought an incisive, inquisitive mind to his research, and was often responsible for the astute question that would push an investigation in the right direction,” noted Rockefeller President Richard P. Lifton in a message to university faculty and staff. “He enjoyed the camaraderie of his fellow scientists, served as an informal mentor to many junior faculty members who sought his advice, and was an active member of the Rockefeller community until very recently.”

Born in Frankfurt in 1933 during the rise of the Nazis, Model and his parents escaped in 1942 to settle in New York. As a young man, he studied economics at Cornell University and Stanford University, served in the United States Army as a first lieutenant, and worked in his father’s investment banking business for a period before earning a Ph.D. in biochemistry from Columbia University.

“Peter was a remarkable person who straddled many worlds,” says Jeffrey V. Ravetch, Theresa and Eugene M. Lang Professor and head of the Leonard Wagner Laboratory of Molecular Genetics and Immunology at Rockefeller, who was a student in Model’s lab in the mid-1970s. “Perhaps because of his background in economics and finance, he had a different way of looking at things, and he became a great champion of using new approaches in the lab. He was viciously smart, and he always valued substance over style.

“When many other people began working with mammalian systems, Peter stuck to his focus on bacterial genetics and remained true to the essence of microbial systems,” Ravetch adds. “He saw that they would continue to yield valuable discoveries.”

Model arrived at Rockefeller in 1967, joining the laboratory of the late Norton Zinder as a postdoctoral fellow. Named assistant professor in 1969 and associate professor in 1975, he was promoted to full professor in 1987. He and Zinder worked closely together in the laboratory, and Model became co-head of the lab in 1987. From 1992 to 1995, he also served as associate dean of curriculum under deans Bruce McEwen and later Zinder.

Bacterial viruses, or phages, are among the simplest of biological entities and contain only a handful of genes. Model’s work with them opened a number of new lines of research. He championed the use of several modern molecular genetic techniques, and used these methods to examine, among other things, how phage proteins translocate across bacterial membranes. He developed phage display, which became a widely used method for identifying interactions between proteins. Using this and other techniques, he explored key biochemical processes in the lifecycles of phages.

Model’s strong commitment to the education and training of younger scientists led him to serve as the primary advisor for a number of graduate students and postdocs during his tenure at Rockefeller.

“Peter had a way of asking questions that could change the direction of research,” says his wife, Rockefeller associate professor Marjorie Russel, with whom he collaborated. “He was famous for incorporating his knowledge from diverse areas and putting everything together in ways that no one else had ever thought of before. Often, after talking to Peter, his students and colleagues would go back to their lab benches with completely new ideas about what to do and where to go with their research.”