Frozen in time: Flexner’s historic lab re-opens with early inventions on display

If these walls could talk. The historic lab on the first floor of Flexner features benches, fume hoods (above, right) and other lab equipment from the 1950s. Carrel-Lindbergh perfusion pumps (above, left), invented by a Rockefeller scientist and manufactured in the university’s former glassblowing shop, are among the instruments on display.

by LESLIE CHURCH

You don’t always know you’re making history when it’s happening. But it’s a good idea to hang on to all the evidence, just in case. That’s exactly what Merrill W. Chase did when he began collecting instruments invented at Rockefeller throughout the twentieth century. And it’s what led the university to preserve a piece of Flexner Hall when the latest renovations started in 2010.

A newly reconstructed historic lab in Flexner will feature some of the more than 300 instruments that Dr. Chase, who joined the university in 1932, collected in his 70-plus years here. Housed on Flexner’s first floor, the lab also contains benches, bookshelves and fixtures dating as far back as the building’s construction in the early twentieth century.

The idea for the lab started in the 1990s, when the sixth floor of Flexner was converted to offices for emeritus professors. The university thought it would be a good idea to keep one of the labs — Lyman C. Craig’s — intact, and Peter Sellers, curator of the Chase collection, started keeping instruments in it. When designs for the new Flexner were laid out, the move to the first floor seemed obvious.

“We think this is a great part of the building’s history, and we wanted it to be more prominent,” says George Candler, associate vice president for planning and construction. “We kept pieces from several of Flexner’s labs and stored them offsite until most of the construction was done.”

The new space has been outfitted with large windows so that passerby can get a glimpse into what a lab looked like in the early twentieth century. Before plastic.

“The university had a glassblowing shop, a woodworking shop and a machine shop,” says editor and author Carol Moberg, a senior research associate in the Steinman laboratory. “The scientists would get together with the master craftsmen and create tools to solve problems. The glasswork is especially beautiful.”

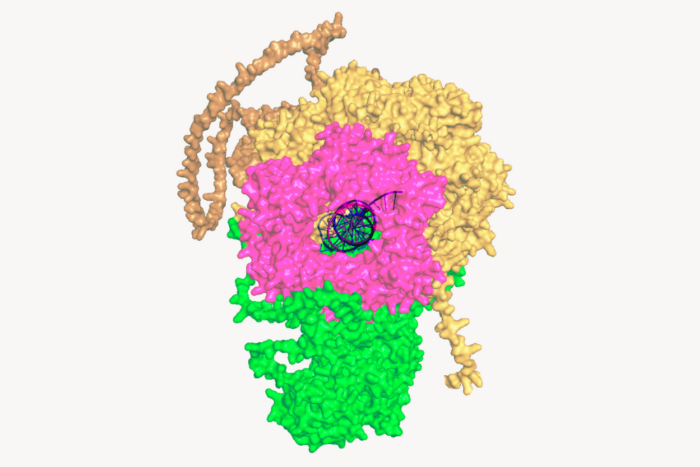

Almost everything in the lab — from the fume hoods to the air and gas nozzles to the heavy stone bench tops that are twice as thick as the modern ones — comes from the old Flexner labs. Only the ceiling lamps and the retro black and green checkered floor were redone to mimic the building’s original design. The room is speckled with sculpture-like glass instruments so delicate that it’s hard to believe they were used in experiments at all.

Lined up in a row on one shelf are seven glass perfusion pumps invented by Rockefeller’s Alexis Carrel and the aviator Charles Lindbergh. The pumps, dated to the 1930s, were used in animal experiments to keep whole organs alive outside of the body. Mr. Lindbergh’s sister-in-law had heart problems that were untreatable because technology at the time did not allow for organs to be removed and preserved during surgery. The pumps are precursors of the heart-lung machines used in open heart surgery beginning in the 1950s.

“The progress of science depends on the invention and refinement of tools and techniques,” says Dr. Moberg. “As the technology gets more sophisticated, it can answer more questions.”

Other instruments on display include a small hand-operated glass prototype of a countercurrent distribution apparatus developed by Dr. Craig; a Pyrex conductivity cell, designed by Theodore Shedlovsky, for studying the conductance of concentrated solutions; and an angle centrifuge, adapted from a Swedish design, developed by Rockefeller instrument maker Josef Blum in the 1930s.

Currently open for viewing only by appointment, the lab debuted in February with an exhibit on R. Bruce Merrifield, the Rockefeller scientist who won a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1984 for the development of solid phase peptide synthesis. The lab currently features instruments discussed in Dr. Moberg’s recent book, Entering an Unseen World, which explores the legacy of a Rockefeller lab that helped create the field of modern cell biology.

“We have an amazing history here,” says Olga Nilova, outreach and special collections librarian. “It’s important for us to preserve it and also to share it with the scientists who are here today. It reminds them of the value of the work they’re doing right now.”

To make an appointment to go inside the lab, contact Dr. Moberg or Ms. Nilova.