Leslie Vosshall promoted to professor

The university’s Board of Trustees has granted tenure to Leslie B. Vosshall, head of the Laboratory of Neurogenetics and Behavior, and she has been promoted from associate professor to become the Robin Chemers Neustein Professor. The Board approved the promotion at its March 10 meeting.

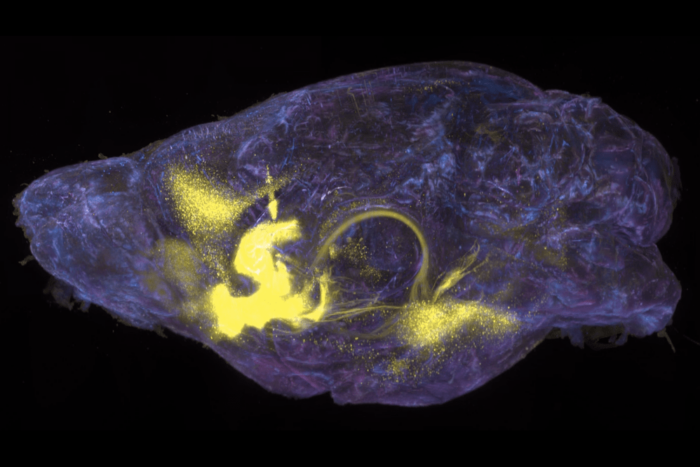

Vosshall’s research focuses on the mechanism of smell, a critical sense that underlies an organism’s ability to detect food, find mates and avoid predators. She has investigated how flies, mosquitoes and humans are able to perceive and process odor stimuli and how they can discriminate between thousands of different odors in the environment. In the case of mosquitoes, she is also interested in learning to manipulate the odor-sensing mechanism in order to prevent the insects from being able to detect — and spread disease to — human hosts. In work that was published in Science in 2008, she discovered the mechanism by which the widely used insect repellent DEET blocks mosquitoes’ ability to locate their prey.

Recently her lab has expanded its scope to ask questions about how smell is linked to behavior, both in insect models and in humans. “When the lab first started we were narrowly focused on the mission of describing the fly olfactory system: finding all the chemosensory receptors that allow flies to smell odors, carbon dioxide and pheromones; mapping circuits into the brain; figuring out how the insect chemosensory receptors worked at a functional level,” Vosshall says. “In recent years, we have begun to ask more integrative questions involving the human sense of smell and also how innate insect behaviors — like responding to smells, finding food and having sex — are modulated by internal physiological states. We want to understand how the insect brain decides when to eat and when to stop eating, whether that insect is a Drosophila fly looking for yeast growing on fruit or a hungry female Aedes mosquito looking for a human blood meal.”

Vosshall, who was originally inspired to study science by her uncle, retired Syracuse University physiologist Philip Dunham, chose neuroscience because it has allowed her to ask questions not only about physiology but about behavior and genetics. She came to the university as a graduate student, where she studied in Michael Young’s laboratory, and received her Ph.D. in 1993. She then did postdoctoral work at Columbia University, in Richard Axel’s lab, but returned to the East Side a few years later, becoming assistant professor at Rockefeller in 2000. She was promoted to associate professor in 2006 and was named a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator in 2008.

Vosshall has been the recipient of awards from the John Merck, Beckman and McKnight Foundations. She received the 2002 Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers, a 2005 New York City Mayor’s Young Investigator Award for Excellence in Science and Technology, a 2007 Blavatnik Award for Young Scientists, the 2009 Lawrence C. Katz Prize from Duke University and a 2010 Dart/NYU biotech award.

“I’m very excited about our new mosquito projects,” Vosshall says. “The mosquito is an understudied model system of great medical importance. I hope we can make some significant contributions in the next decade to understand how and why female mosquitoes are so good at hunting humans.”