Paleovirology expanded: New virus fragments found in animal genomes

Understanding the evolution of a virus can help beat it. This is immediately true in the fight against the ever-changing influenza bug, and potentially so in ongoing battles against Ebola and dengue fever, too. New research now points the way to a fossil record of viruses that have surprisingly insinuated themselves into the genomes of insects and animals, providing clues about their evolutionary history. The findings, to be published online August 18 by PLoS Genetics, could enable scientists to learn from genetic “fossils” of viruses in much the same way that they do from retroviruses, which unlike regular viruses, use their host’s genetic machinery to reproduce.

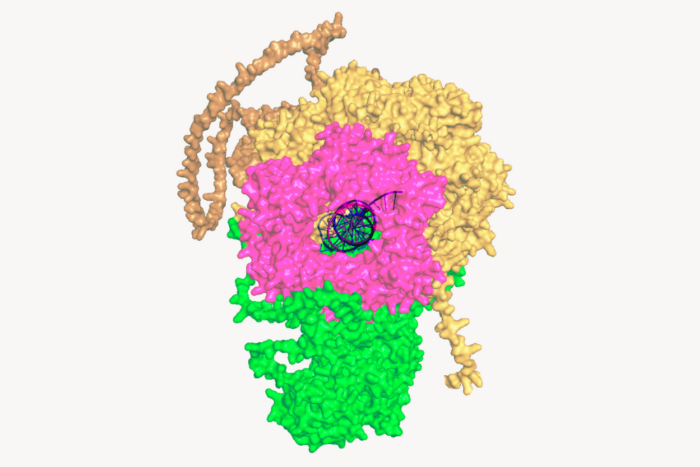

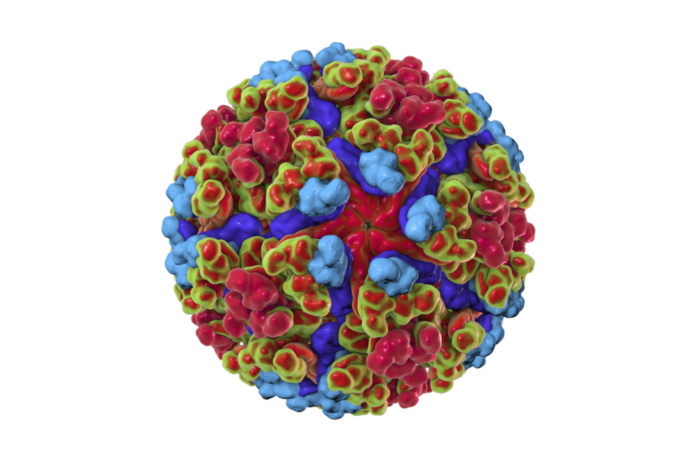

Robert Gifford, Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center assistant professor at Rockefeller University, led the research, which used the rapidly advancing technology for genetic screening to analyze a database of insect, bird and mammal DNA for fragments of virus genomes, named endogenous viral elements (EVEs). Working with colleague Aris Katzourakis from the University of Oxford, he discovered representatives of ten families of viruses, including hepatitis B, Ebola, rabies and dengue and yellow fevers.

“This has really only become practical because of the scale of sequencing that’s been done,” Gifford says, referring to the reference genomes of the animals that he matched against those of different viruses. “In some cases, we’ve got the first evidence of an ancient origin for some of these virus groups.”

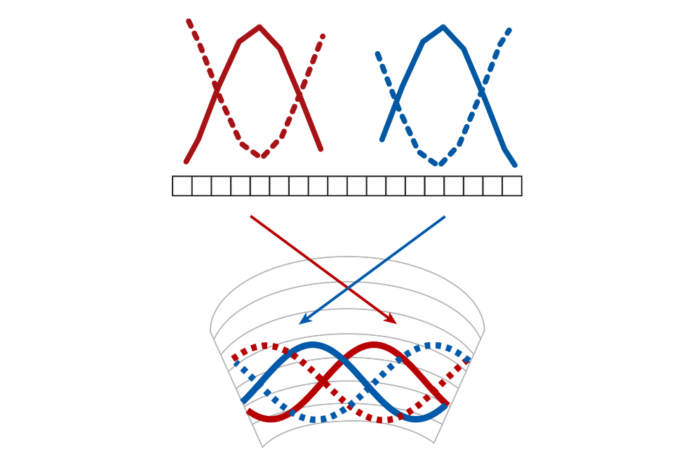

Since the 1970s, scientists have found the genetic signatures for retroviruses in animal genomes, a discovery explained by the fact that retroviruses (such as HIV) integrate into their hosts’ chromosomal DNA in the process of reproducing themselves. In humans, retrovirus fossils account for as much as eight percent of our DNA. This fossil record has allowed researchers to trace the ancestry of some of these viruses, and in some cases even determine what was responsible for killing them off.

The diversity of new viruses discovered in animal genomes includes the first endogenous examples of double-stranded RNA, reverse transcribing DNA and segmented RNA viruses, and the first DNA viruses in mammals. The findings suggest that scientists will eventually be able to recover genetic fossils for many, if not all virus families, greatly broadening the scope of paleovirological studies. “It’s the tip of the iceberg,” Gifford says.

Much remains to be learned about endogenous viral elements, including exactly how these virus fragments find their way into nuclear DNA. Most of the fragments documented by Gifford are no longer functional, appearing like what is commonly referred to as junk DNA. But Gifford says the findings suggest that some of these virus fragments have been co-opted by their hosts at some point in their evolutionary history, perhaps as a defense against related infections.

In particular, Gifford says that finding endogenous viral elements in insect genomes promises to reveal a new dimension in paleovirology, allowing scientists to probe the relationship and evolution of the virus, its vector and host, potentially providing insight into the complex ecological relationships that underpin insect-borne diseases.

|

Public Library of Science Genetics online: November 18, 2010 Endogenous Viral Elements in Animal Genomes Aris Katzourakis and Robert J. Gifford |