Researchers track fish migration by testing DNA in seawater

Scientists analyzed DNA samples in water collected from New York’s East and Hudson Rivers to track fish migration.

A bucket of seawater contains more than meets the eye—it’s chock-full of fish DNA. Scientists are now putting that DNA to good use to track fish migration with a new technique that involves a fraction of the effort and cost of previous methods.

DNA strained from samples drawn weekly from New York’s East and Hudson Rivers revealed the presence or absence of several key fish species passing through the water on each test day. Published in PLOS ONE, the findings correlate with knowledge from migration studies conducted over many years with fishnet trawls.

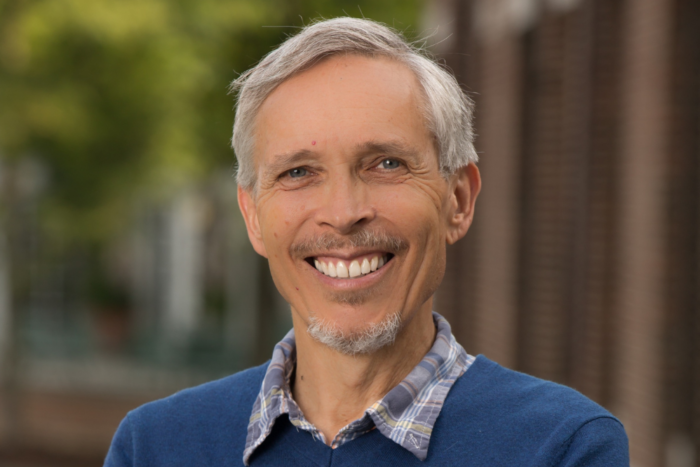

“For the first time, we’ve successfully recorded a spring fish migration simply by conducting DNA tests on water samples,” says Mark Stoeckle, senior research associate in the Program for the Human Environment. Using this method to estimate the abundance and distribution of fish species could help scientists more easily understand the impact certain environmental factors, such as oyster farms or pollution, are having on local fish populations.

As they swim, fish leave traces of their DNA in the water, sloughed off their gelatinous outer coating or in excretions. Previous research had shown that relatively small volumes of freshwater and seawater have enough of this DNA, termed environmental DNA (eDNA), floating in them to detect dozens of fish species.

The researchers were able to identify 42 fish species by analyzing eDNA extracted from water samples, including most of the species known to be locally abundant or common, and only a few of the uncommon ones. The amount of eDNA from the various species identified roughly corresponded with data from net surveys.

“We didn’t find anything shocking about the fish migration—the seasonal movements and the species we found are known already,” says Stoeckle. That’s actually good news because it shows that the eDNA method is a good proxy to the traditional ones.

Stoeckle conducted the research with Zachary Charlop-Powers, a visiting scientist in Laboratory of Genetically Encoded Small Molecules, and Lyubov Soboleva, a high school student participating in Rockefeller’s Summer Science Research Program.

Stoeckle and colleagues say the new method could potentially offer several advantages. Analyzing eDNA is cheap and relatively easy, and it allows scientists to collect samples without disturbing or harming the fish. But they also note that further comparisons with traditional surveys will need to be made to establish the technique’s accuracy and reliability.

“If future research confirms that an index of species’ abundance can be derived from naked DNA extracted from water,” says Jesse Ausubel, director of the Program for the Human Environment, “it could easily improve the rationality with which fish quotas are set, and the quality and reliability of their monitoring around the world.”