No borders to excellence: Rockefeller’s graduate students come from everywhere, including Cuba

by Wynne Parry, science writer

Students arrive from around the world to join Rockefeller’s graduate program; the ratio of international students is higher here than in most equivalent programs in the United States. This year’s entering class has a particularly global character. Of the 27 students, more than half are from abroad.

They come from Austria, Belgium, Canada, China, India, Peru, Singapore, Switzerland, Thailand, the United States—and Cuba. Physicist Frank Tejera is first student in the program to enroll directly from the communist nation, an accomplishment that required an unforeseen thawing between the two countries, impeccable timing, as well as a great deal of patience and some creativity.

“Private financial support of the graduate program allows us to recruit the best students from all over the world,” says Emily Harms, Associate Dean for Graduate Studies. “As a result, the international diversity of our graduate program is one of its greatest strengths. It is always rewarding to welcome a new group of promising students from a variety of backgrounds to Rockefeller.”

A very long shot

In March of 2014, roughly nine months before U.S. President Barack Obama and Cuban President Raul Castro announced the restoration of diplomatic ties between the two nations, Mr. Tejera, a physicist and teacher, attended a conference at the University of Havana, where he worked. There, he heard Marcelo Magnasco, a professor and head of Rockefeller’s Laboratory of Mathematical Physics, discuss a physics-based approach to understanding leaf venation and the formation of other vascular networks. Fascinated, Mr. Tejera offered to give Dr. Magnasco a tour of the laboratory in which he was working.

Before Dr. Magnasco’s talk, Mr. Tejera had never heard of Rockefeller; access to information about the United States was extremely limited. “I knew there were a lot of important universities, but nothing else. Normally, in Cuba, once you finish your bachelor’s and master’s degrees, you apply to European schools,” he says. “I was lucky to have this opportunity. But during the process, I didn’t have much hope.”

Even after the announcement of a new relationship between the countries, many bureaucratic and logistical barriers remained. To name a few: Shortly before the deadline, he was unable to connect to the university’s online application—internet access was extremely limited at best—and had to ask a colleague in Mexico to complete the application for him. Then, delays receiving his travel visa prevented him from attending interviews and other events the Dean’s Office schedules for interviewing students.

“I want to emphasize the flexibility the Dean’s Office displayed in dealing with these difficulties,” Dr. Magnasco says. “It would have been very easy to say, ‘this is a difficult case, we don’t need to bother with it.’ But that approach doesn’t work, because we need to find exceptional people, no matter where they are and whether or not they fit the standard profile.”

Dolphins and ants

In December, Mr. Tejera was finishing up work on a camera that records the world the way a dolphin likely sees it, as part of a research project into the animals’ cognition.

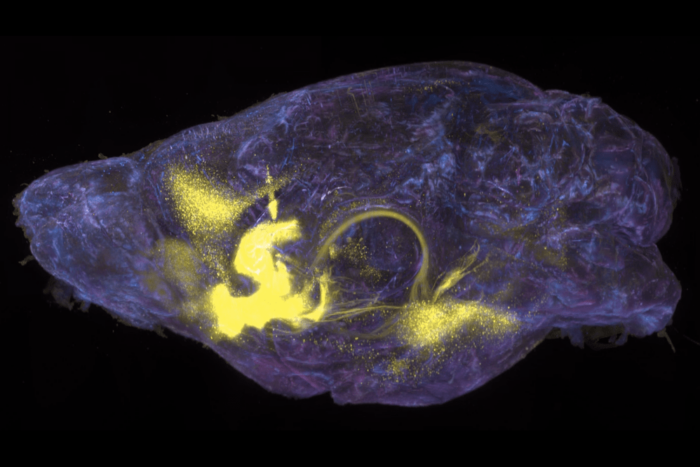

As the winter break approaches, Mr. Tejera is finishing up his first laboratory rotation with Dr. Magnasco’s group. His project is to build a camera that records the world the way a dolphin likely sees it, sensing the blue, green, and violet wavelengths of light that penetrate deep water. This swath of the spectrum only partially overlaps with the blue, green, and red to which human eyes respond. Dr. Magnasco intends to use the camera as part of his work studying dolphin cognition.

As he looks forward to taking on other projects, including work with ants in Daniel Kronauer’s Laboratory of Social Evolution and Behavior, Mr. Tejera says he appreciates the intellectual freedom he has found at Rockefeller.

“Everything is very open here,” he says, “When I get an assignment I am given the opportunity to accomplish it with the support and resources I need.”

Settling in

Mr. Tejera’s adjustment outside the lab and classroom, to a new city and new country, has required some flexibility on his end, as well as assistance from people in the Rockefeller community. Some practical issues—health insurance, credit cards—were entirely new to him, as was the pace of life in New York City. “I need more time than 24 hours a day to live here,” he says.

Still, things have gone well, and he suspects other young scientists and others will follow in his footsteps. “In two to three years, I think there will be a lot of Cuban students in the U.S.,” he says.